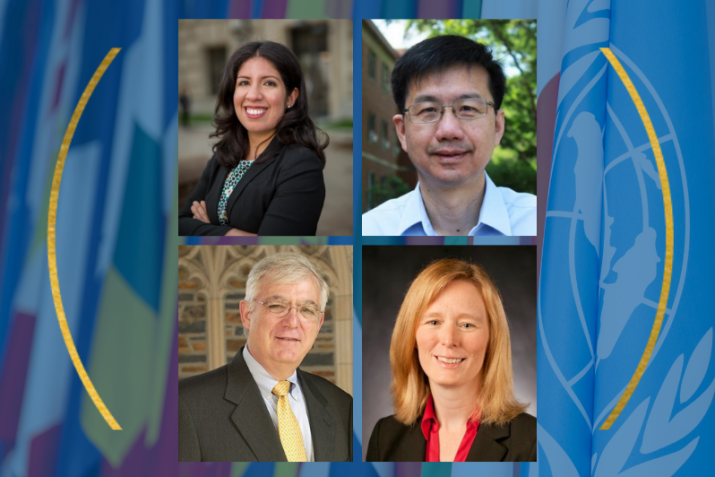

Clockwise from top left: Duke global health experts Andrea Thoumi, Shenglan Tang, Michael Merson and Sarah Bermeo.

Published December 2, 2020, last updated on December 8, 2020 under Around DGHI

In July 2020, President Donald Trump announced plans for the U.S. to withdraw from the World Health Organization, which he has repeatedly blamed for failing to contain the spread of the novel coronavirus. While the threat had no immediate practical effect – the WHO’s rules require a year’s notice to withdraw – it inflamed concerns in global health circles that the U.S. would back away from its historical commitment to the organization at the worst possible time.

Following the election of Joe Biden as president, most of those same people expect a reset in the U.S.’s relationship with the WHO. But what damage has been done? And what should guide the Biden administration as it moves to re-engage with the WHO?

We posed those questions to four Duke experts, all with plenty of experience with the WHO and global health financing and policy:

- Sarah Bermeo is an associate professor of public policy and political science who studies U.S. foreign aid policy and the political economy of international development.

- Michael Merson is the Wolfgang Joklik Professor of Global Health at Duke and DGHI’s founding director. He worked with WHO for 17 years and directed the WHO’s Global Program on AIDS from 1990-1995. He currently serves as director of the SingHealth Duke-National University of Singapore (NUS) Global Health Institute.

- Shenglan Tang is the Mary D.B.T. and James Semans Professor of Population Health Science at Duke and DGHI’s deputy director. An expert on health systems reform and disease control, Tang has done research and analysis for many international organizations, including the WHO, over the past three decades.

- Andrea Thoumi is a health equity policy fellow at the Duke-Margolis Center for Health Policy whose research includes health policy and health financing, vaccine access and global health.

Here are their responses, edited for length and clarity:

DGHI: What is the current state of the U.S.’s relationship with the WHO? Is it as bad as the rhetoric has made it seem?

Sarah Bermeo: One could say that the best word to characterize the current U.S. relationship with the WHO is “uncertainty.” The Trump administration announced in July that it would withdraw from the WHO, but rules for withdrawal mean that this could not officially happen until a year later, in July 2021. President-Elect Biden declared during the campaign that he would reverse the decision, so it appears unlikely the U.S. will actually withdraw. But it is unclear what path the Trump administration will pursue in its remaining months in office. Moving forward, the Biden administration cannot fully undo the sense of uncertainty regarding the U.S.’s long-term commitment to the WHO and other global institutions.

Shenglan Tang: While I agree with the concerns Sarah has raised, I am confident that the Biden administration will be able to recover the damaged relationship between the U.S. and the WHO after Jan. 20 when Biden takes office. As Sarah noted, legally the U.S. has not yet withdrawn from its membership of the WHO.

Michael Merson: On a working level, collaboration remains strong. Many Americans are working with colleagues at the WHO. There is much tension at a political level, but this will hopefully begin to resolve when President Biden takes office. Relationships remain very strong with the Pan American Health Organization, a regional office of WHO.

DGHI: How has the U.S. pullback from the WHO affected efforts to control the pandemic, both in the U.S. and globally?

Andrea Thoumi: Historically, the United States has been the WHO’s leading donor. While the official pullback from the WHO would not have happened until July 2021, the U.S. only paid half of its dues this year. Given the U.S.’s leading funding role, a complete withdrawal would have compounded the already detrimental effects we’ve seen in so many prevention and treatment programs that have occurred due to the pandemic.

Shenglan Tang: I would also point out that The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the United Kingdom government and other European countries have increased their financial support to the WHO significantly after the Trump administration decided not to cooperate.

Michael Merson: The WHO has received considerable support from other governments so the threat of the U.S. withdrawal has not had a serious impact.

DGHI: Has the U.S.’s combative stance affected the WHO’s work on other areas?

Sarah Bermeo: Once the Trump administration announced its plans to withdraw from the WHO, it set in motion a process that took effort away from other priorities, including the current pandemic and other WHO activities. Staff at the WHO were obliged to react not only to the possible forthcoming withdrawal, but also to the threat by the Trump administration to reallocate currently due money. Even the uncertainty created by the possible withdrawal of funds would create the need for contingency planning across multiple programmatic areas and would have hampered medium- and long-term planning.

DGHI: The Biden administration has already said it will not revoke U.S. funding from the WHO. What does that signal for the potential for renewed collaboration?

Michael Merson: It is a very positive sign that the U.S. government will not withdraw from WHO. But it is likely that the U.S. will request reforms that strengthen WHO’s operations, particularly with regard to pandemic control.

Andrea Thoumi: Most immediately, this positive signal will hopefully translate into renewed collaboration to address COVID-19 as the global public health crisis that it is and provide the needed global coordination and stewardship for other prevention campaigns.

Sarah Bermeo: This affects not just collaboration but the ability to carry out programmatic activities around the world. In signaling that he will not revoke funding, President-elect Biden is ensuring that the U.S. will maintain a place at the table when decisions are made. This is important not just during the current pandemic but going forward.

If the U.S. remains a large funder of the WHO, and if U.S. scientists remain engaged in research and operations, then the U.S. can have significant impact on the future rules and operations of the organization. To the extent that mistakes were made in the global response in this pandemic, the U.S. will have a say in reforms for the future.

Shenglan Tang: Under the Biden administration, I am sure that the U.S. will be able to continue to play an important role in global health and influence what WHO will be doing. The three largest funding organizations of the WHO are the U.S., the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the U.K. government, and it is certain the U.K.’s funding will be cut significantly. Remember that U.S. researchers have actively participated in Gates-funded projects/programs managed by WHO. So I personally don’t think that the U.S.’s influence on WHO would reduce significantly in years to come.

DGHI: Is there a good chance now that the U.S. could join COVAX, the multinational partnership, to ensure equal access to a Covid vaccine?

Michael Merson: Yes, this is very likely to occur and is in the best interest in ensuring access to COVID-19 vaccines in low-income countries.

Shenglan Tang: I agree that the Biden administration is most likely to join COVAX. However, I don’t have confidence in equal access to a COVID vaccine among different countries and among different socio-economic groups within a country, due to the past experiences and the healthcare systems in operation.

Andrea Thoumi: Yes, there is a good chance that the Biden administration will join COVAX as it aligns with the administration’s plans for providing global health security leadership, including the immediate re-establishment of the National Security Council for Global Health Security and Biodefense. COVAX not only supports science, but also provides a critical financing mechanism to mitigate equity concerns regarding distribution of and access to vaccines for COVID-19 among low- and middle-income countries. I agree with Shenglan that addressing equity concerns among countries may not translate to the prioritization of communities with the highest burden of COVID-19 transmission or mortality within countries.

DGHI: Some say the U.S. failed the international community when Trump said it would revoke its contribution to the WHO. What will the U.S. need to do to regain the trust of the global community in its relationship with the organization?

Sarah Bermeo: The announced withdrawal from the WHO is part of a broader pattern that also saw the Trump administration withdraw from international agreements such as the Paris Climate Accords, the Trans-Pacific Partnership and the Iran nuclear deal, and work to weaken other institutions such as the World Trade Organization. One positive for the Biden administration is that many Republican senators felt the Trump administration went too far in disengaging from the global community. There is likely to be an opportunity for bipartisan support when it comes to reengaging with global institutions.

A key difficulty will be global wariness in relying too much on U.S. leadership, even if world leaders are inclined to give the Biden administration the benefit of the doubt. Other countries must consider what might happen in the next U.S. presidential election. By showing the fragility of U.S. leadership and willingness to invalidate prior agreements even over the objection of Congress, the Trump administration has done lasting harm to the credibility of the U.S. government in international relations. Trust takes time to build and it is only partially in the hands of the incoming administration.

Michael Merson: President Biden has already indicated his intent to strengthen our multilateral involvement with international organizations and alliances. Those individuals whom he has nominated for leadership positions in the area of global security have a strong background in multilateralism.

DGHI: The Trump administration has been critical of the speed of WHO’s response to COVID-19 and its relationship with China. Is there any basis for their critique? Should the Biden administration push the WHO for improvements in any areas?

Michael Merson: I believe it likely that the Biden administration will do this. Many governments would like to see such improvements, including a revision of the International Health Regulations.

Sarah Bermeo: The Trump administration is not alone in criticizing parts of the WHO’s response to COVID. Some experts believe the early response was not critical enough of China’s initial handling of the outbreak. However, the leadership of the WHO is in a difficult position. The WHO is made up of 194 countries and operates within those countries with the permission of the home government, making criticism difficult and potentially counterproductive when keeping teams on the ground is important.

Other criticisms of the WHO response include its conflicting early recommendations on mask wearing, slow uptake of recommendations to endorse the use of cloth face coverings, and hesitation to admit the likelihood of aerosol transmission of SARS-CoV-2. The Biden administration and other member countries should work with the WHO leadership to determine more effective pathways to curtail future pandemics and consider alterations to its bureaucratic decision-making that would alter the speed and processes by which scientific recommendations are updated as a crisis unfolds.

Shenglan Tang: The WHO should have done as it did during the early stage of the first SARS epidemic in 2003. The WHO challenged the government of China on its delay in reporting SARS cases, and in doing so, it won respect from around the world. Unfortunately, this time, the WHO, and particularly the WHO China office, did not provide the public in China with any useful information on its website, only repeating what the Chinese government said up until Jan. 20. Even the public in China was not happy with WHO this time.

DGHI: What else should the Biden administration be focused on with regard to its relationship with the WHO?

Michael Merson: It would be helpful in time for the Biden administration to examine the value and impact of U.S. government support to WHO in areas other than pandemic control, as well as the overall governance structure of the WHO.

Andrea Thoumi: The Biden administration should begin to view the relationship with the WHO as one of supporting a public good. Yes, the WHO needs reform, but at its core, the WHO provides a backbone to providing core functions for public health. These core functions include monitoring, coordination, and leading action and research in health areas that otherwise would not receive a global response. For example, the WHO provides critical information on outbreaks around the world to member countries. Many countries also rely on the WHO to provide leadership and evidence-based recommendations through new screening or treatment guidelines that support countries and advance their health agendas and technical programs.

In addition, the Biden administration can improve awareness of the progress that U.S. contributions have made and how Americans benefit from global collaborations. For example, the WHO’s work on controlling epidemics like HIV, polio and increased investments in maternal and child health, have been vital to the lives saved we’ve seen in the last two decades. The WHO also has a network of collaborating centers for technical collaboration on key health areas like surveillance and biosecurity.