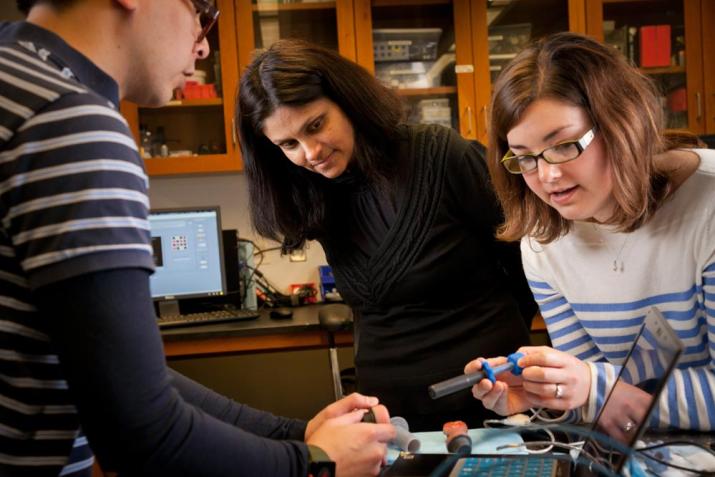

Doctoral students Christopher Lam and Jenna Mueller work alongside Nimmi Ramanujam to develop new technologies for detecting cancer.

Published September 15, 2014, last updated on April 6, 2020 under Research News

This story is featured as part of the Duke Today series on Duke's Entrepreneurial Spirit

In the corner of a lab packed with computers and equipment, PhD student and Global Health Doctoral Certificate Christopher Lam stands at a workstation decorated with photos of his dog wearing a Duke head scarf or safety goggles. He gestures toward a colposcope — a stereo microscope almost as tall as he is — that uses reflected light to screen for cervical cancer. “Imagine being a health worker in a setting like Haiti, and you have to carry something like this on the back of a motorcycle,” he says.

Lam and others in the Tissue Optical Spectroscopy (TOpS) Lab are working on an entrepreneurial alternative to the giant device, one they hope will help improve women’s health across the developing world. They have been developing a vastly smaller colposcope, one shaped like a tampon that can connect wirelessly to a tablet or smartphone. Inspired by a spy pen, the device would enable women to take pictures of their own cervix and send them to their physicians, eliminating the need for a physical exam at a potentially distant clinic.

A hand-held colposcope is just one of several technologies coming out of the lab team led by Nimmi Ramanujam, the Robert W. Carr, Jr., Professor of Biomedical Engineering at the Pratt School of Engineering. She is also global health faculty member and leads Duke's Center for Global Women's Health Technologies (GWHT). An entrepreneur, teacher and mentor, Ramanujam is pursuing new cancer-screening technologies and other innovations while training students how to move nimbly between the lab and the marketplace to serve women in some of the world’s poorest communities.

Engineering Novel Technologies in Cancer Care

Her start-up company, Zenalux, “translates the lab’s technology into something that can be used in the field,” says Jesko von Windheim, the company’s CEO and a professor of the practice at the Nicholas School of the Environment.

The company’s Zenascope, for example, detects cancer in early stages and monitors whether therapies are working by shining light on tissue and measuring how wavelengths are scattered or absorbed. The results can reveal how much oxygenated blood is in body tissues or how well drugs are concentrating within tumors.

“The idea is that a surgeon will use this tool while operating to look at excised tissue from the breast to see if there is cancer on the surface or below it. If there is, he or she knows to cut out more tissue,” Nichols says.

Surgeons now typically send tissue to a pathologist to examine under a microscope for signs of residual cancer. The process can take several days and may result in the need for a second surgery, which is expensive and gives the cancer more time to spread. The new approach could change the clinical standard of care.

Nichols and Schindler have been fine-tuning their invention in the clinic and attending Zenalux meetings to learn what it takes to translate technology into usable products. “This experience definitely makes me want to be an entrepreneur,” Nichols says.

“The aim isn’t to create a bunch of entrepreneurs, but to make them aware that entrepreneurship is part of the process through which technologies make it to the community at large. That’s the real goal,” Ramanujam says.

Engaging Young Kenyan Girls in Engineering

Two more of her students are pursuing still another project in Muhuru Bay, Kenya, the site of an ongoing Duke program. The previous summer, as part of their fellowship with Duke’s Center for Global Women’s Health Technologies, which Ramanujam founded, rising seniors Mikayla Wickman and Kendall Covington created an engineering club for girls at the Women's Institute for Secondary Education and Research (WISER). WISER is a boarding school that also has programs to provide local residents with clean water, better nutrition and health care.

Wickman and Covington worked with 53 teenage girls to build circuits and combine them with items such as water bottles and plastic folders to create mechanically powered light sources — including flashlights, headlamps and lanterns — for students to use during blackouts. The club members now want to use their newly acquired skills to construct light sources for the labor and delivery room in the town’s clinic.

The GWHT fellows are working to make the club self-supporting. “We asked ourselves, how can we make this project sustainable?” Covington says. “We want to empower the girls and give them responsibility for their club.”

The WISER students plan to custom-design specialized light sources for clients. Once they have refined their designs, they will sell the light sources to the community at affordable prices. They’ll use the profits to purchase materials for more light sources and to expand into other products, such as radios that future GWHT fellows will teach them to build.

“I’d never considered entrepreneurship as something we could do, but all of a sudden it seemed like the next logical step,” Wickman says.

Until the venture becomes fully sustainable, Wickman and Covington are fundraising at home to provide the club with supplies. They’re also collecting items such as motors, LEDs and cell phone batteries from old machines that would otherwise be thrown away, and sending these to WISER.

“A lot goes to waste here,” says Covington. “Our experience in Kenya taught us how resourceful we can be with materials we often discard.”

While Ramanujam mentored Wickman and Covington through the experience, she gives them full credit for the club’s success. “They created the manual, they created the lessons, they figured out how to change things when they did not work, they made all of the executive decisions,” she says. “Most importantly, they formed relationships and played important leadership roles in addition to teaching engineering.

“This is what is most satisfying for me as a mentor: Seeing students gain a sense of ownership and leadership,” Ramanujam adds. “We’re all entrepreneurs, but what takes us to the next level is seeing the need for change — and acting on it.”