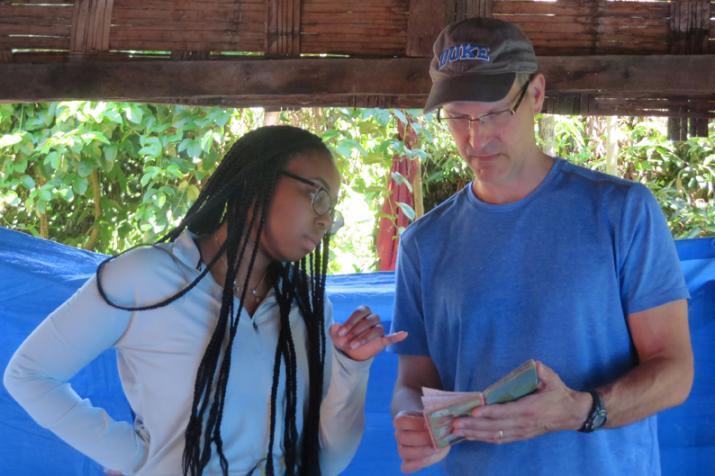

Charles Nunn, professor of evolutionary anthropology and global health, reviews information with a student in the field.

Published September 19, 2019, last updated on April 7, 2020 under Education News

A Duke Global Health Institute summer research project can involve eight to 10 weeks of living, learning, and working in a different cultural environment. Sometimes that can mean sleeping in a tent with no running water or electricity in a remote region far from home. For Charles Nunn, a professor of evolutionary anthropology and global health who regularly mentors students performing fieldwork, this is when the cheerleader in him kicks into gear.

“I am constantly trying to put myself back in their shoes,” says Nunn. “Particularly when students are in the field, my role can be to provide a bit of a pick-me-up when things are challenging. I do that by helping students see the big picture and how they’re making progress.”

Nunn mentors vertically integrated teams of students doing fieldwork in Madagascar each summer. Teams may include undergraduates, students in the Master of Science in Global Health program, postdocs and medical students. In 2019, Nunn won DGHI’s outstanding undergraduate professor award based on student nominations.

For both Nunn and Vissoci, learning from their students’ curiosity and research is tremendously rewarding, and empathy is as much a hallmark of their approach to mentoring as sharing rigorous research methodology.

He is actively involved in his students’ preparation for fieldwork and research. He encourages students to have ownership of their projects, with the hope that he is leading them along a path where they can explore the questions that are of interest to them. This may involve helping students decide on a project, teaching them how to collect data, how to lead discussions, and how to form teams.

Nunn joins the research team in Madagascar for several weeks each summer, but once he returns to Durham, the remote location of the team means that communication is one of the most challenging and the most critical aspects of his work. Despite years of successfully mentoring students in Madagascar, Nunn continues to seek new technologies and strategies to help him stay connected to students thousands of miles away, particularly when students may be exhausted and unable to take a hot shower at the end of the day.

Nunn credits his own PhD advisor as someone who struck the right balance between enthusiasm and criticism as well as freedom and guidance. He uses a similar approach with his own students.

“I try to give concrete, constructive feedback that doesn’t crush them,” says Nunn. “Ultimately, it’s not about patting people on the back, but directing students in how to make science better and teaching them how to discover that process on their own.”

Another award-winning mentor is João Ricardo Vissoci, an assistant professor of surgery, emergency medicine and global health. He mentors research assistants, PhDs, undergraduates and master’s students from the U.S., Brazil and Tanzania. This past spring, he won DGHI’s award for outstanding professor in the Master of Science in Global Health program.

Vissoci draws inspiration for his style of mentoring from his own experience as a student in Brazil and from colleagues at Duke.

“There is a clear difference between the approaches to academic mentoring in Brazil versus the United States,” says Vissoci. “In the U.S., mentoring is one component of academic life, but in public universities in Brazil mentoring is central to academic formation. You build a network and a community as a stepping stone into graduate work. There is no GRE, so the relationships you foster through mentoring directly influence your future academic work.”

He credits his master’s degree mentor for forming his conception of mentoring. “Most of the doors that I have found open to me in my career are because of her,” he says. “We are lifelong friends and colleagues and she is the godmother of my son.”

Vissoci adopted peer-to-peer mentoring after being a part of weekly mentoring sessions with his octogenarian mentor as a PhD student. He also believes in pursuing ambitious goals within a framework of support, a lesson learned from a fellow Brazilian professor who mentored him during his fellowship at Duke.

“He always said, ‘I’ll give you as much work as you want and as you can handle.’ This distinction was important to me,” says Vissoci. “He was saying that he will keep pushing me as long as I can handle it. His influence shifted my entire career into research design and analysis.”

Vissoci often co-mentors students with Catherine Staton, an assistant professor of surgery, emergency medicine and global health whom he describes as a friend and “partner in crime.” Vissoci credits Staton for bringing medical expertise and creative thinking to their collaborative work. “Although we could be seen as peers, I very much consider her a mentor – encouraging me to think broadly and big,” he says. “It is through her influence that I have learned how to handle pressure and to be more effective here at Duke. She always says to me, just sit down and do the work and you will get there.” Vissoci shares these same lessons with his students.

With such a broad range of students under his guidance, Vissoci finds himself providing concrete support to undergraduates whereas PhD students may only want general oversight. Regardless of a student’s level, Vissoci’s driving philosophy remains constant: he strives to be as available as possible and to maintain a fair relationship with all students. He guides not only their academic and career development, but also their human development and growth.

“Conversations with my student can pan out from work to philosophy to society to food to the work-life balance,” he says. “I want students to know that there is more than just work, and those conversations are valuable for students and for me.”

For both Nunn and Vissoci, learning from their students’ curiosity and research is tremendously rewarding, and empathy is as much a hallmark of their approach to mentoring as sharing rigorous research methodology. For students, knowing that someone cares about their personal well-being and believes in their academic future can help contextualize the umpteenth rainy day of their fieldwork. The experience becomes part of their growth on a path toward independence: it’s all part of a bigger picture.