Published November 16, 2010, last updated on March 20, 2013

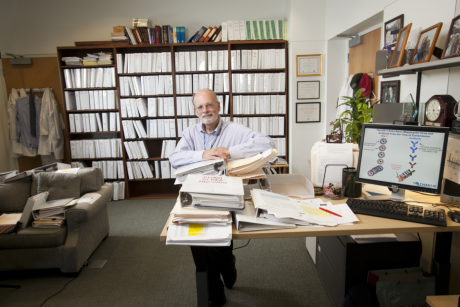

The use of Traditional, Complementary and Alternative Medicine (TCAM) is being realized as a global phenomenon, says a public health researcher from the University of Oxford who gave a lecture at DGHI’s Global Health Exchange series last week. Gerard Bodeker, chair of Global Initiative for Traditional Systems of Health, shared his public health perspective on the globalization of TCAM as a way to prevent, diagnose and treat physical and mental illness.

“What we realized is that our view of modern medicine is alternative medicine in many parts of the world, particularly in the East where we see lower incomes are linked with higher TCAM use,” said Bodeker, also adjunct professor of epidemiology at Columbia University’s School of Public Health, who presented health mapping data on TCAM use. “The WHO Global Atlas on Traditional Complementary and Alternative Medicine was the first birds-eye view of herbal and traditional medicine use around the world.”

Documenting TCAM’s current trends in utilization, sectoral growth and policy, The WHO Global Atlas shows the majority of the world’s population is using some form of traditional medicine on a regular basis, most often herbal medicines. Other WHO data shows 80% of populations in some Asian and African countries are shown to depend on traditional medicine for their primary health care.

As a result of its globalization, TCAM use has raised the public’s awareness, influenced the agendas of medical researchers, regulators and economists and has resulted in increased public financing. “We were struck by this,” said Bodeker, “There’s already solid evidence of the mainstreaming and formalization of these approaches and TCAM is now official policy of the WHO.”

As an epidemiologist who is interested in the public health implications of traditional medicines, Bodeker co-founded the WHO-affiliated Research Initiative on Traditional Antimalarial Methods (RITAM) to study the use of traditional, plant-based antimalarials. The international research network addressed the need for research and policy on the preventive and therapeutic effects of medicinal plants, vector control and repellence. One of its outcomes is the approval of a plant called argemone mexicana as a traditional medicine for the treatment of malaria in Mali.

“I share this outcome because it is an example of how a public health approach to a priority disease in the context of traditional medicine might,” said Bodeker. “This strategy has been effective.”

Bodeker also has research projects studying the effectiveness of herbal home gardens and the use of traditional medicines among refugee populations at the Thai Burma border and among HIV patients in India. He’s also developing training programs for one million rural doctors in China for managing skin disease, and STI’s, and HIV-related illness through integrated modern and traditional medicine.

Another trend Bodeker is watching is the significant use of traditional medicines by women, what he says can signal an important paradigm shift toward the feminization of health care, with a focus on preventive approaches to health and making lifestyle changes rather than the symptomatic, disease-specific approach to health care.