Growing up in Arizona, Alma Solis didn’t have to look far to find an example of overcoming hard circumstances.

Her parents, knowing little English, left Mexico for the United States before she was born. Her father struggled for a sustainable income working in California farm fields, eventually launching his own agricultural business. Her mother, a teacher in Mexico, was not licensed in the U.S. and instead worked a handful of short-lived jobs, including starting her own restaurant selling traditional Mexican foods when Solis was in fourth grade.

“Some days she made a few hundred dollars and others, just one dollar,” says Solis, a PhD student in evolutionary anthropology and a doctoral scholar with the Duke Global Health Institute. “Since there was pressure to improve restaurant sales, I would pass out flyers on the street to potential customers right along the U.S. border in San Luis, Arizona.” Later, she closed the restaurant and worked as a cook and cashier in a grocery store. “She would talk about feeling disrespected and her body would ache from working from long hours in a laborious job.”

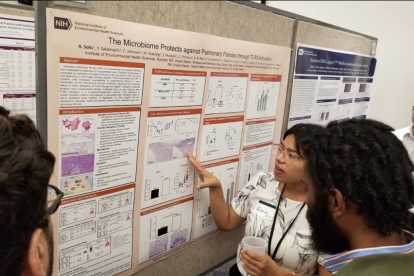

Alma Solis presenting her research as a...

By the time Solis graduated from high school, her mom had taken various courses in a local community college and earned a bachelor’s degree in early childhood education, allowing her to teach again, all while raising four children. She now holds two master’s degrees in education and continues to be her daughter’s source of inspiration.

“I saw my mom go to work early in the morning, come home, go to school and come back later at night to study,” Solis says. “I admired that a lot. I couldn’t wait to go to college like she did. She encouraged me to apply for scholarships, the first with the National Science Foundation.”

Those lessons have not only fueled Solis’ research on health disparities, but also have inspired her to work to widen the path for others into doctoral studies. She’s the driving force behind a series of workshops and panels that peel back the layers of the graduate school application process to make it more accessible for students in underserved and underrepresented populations. The sessions have focused on a range of topics, from how to apply to graduate school and PhD programs to preparing for an interview and writing competitive funding applications for research support.

On Nov. 12, Solis will help lead “Faculty Panel: Applying to Graduate School,” a virtual session for students interested in pursuing a graduate degree in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) fields.

Nearly 200 students from different degree programs and nearby institutions attended the previous talks. The effort also earned Solis the Department of Evolutionary Anthropology’s Mossé Outreach Award this past April.

At the same time, Solis is pursuing her own research, which focuses on the link between anthropogenic changes in land use and the emergence of infectious diseases in Madagascar. She says the DGHI Doctoral Scholars program helps make her interdisciplinary project possible. The program funds up to $12,500 in research for PhD students with a deep interest in global health.

“The stipend was competitive with the cost of living, and it allows me to live comfortably,” Solis says. She also noted the opportunity to work with Charles Nunn, PhD., a DGHI professor. “That’s also what brought me to Duke. Before, I wasn’t sure if I wanted to pursue a PhD until I came across these programs and Nunn’s research in Madagascar.”

Exploring the connections between health and environment is a natural extension of Solis’ own experience. Her parents’ health sometimes suffered because of the nature and conditions of their work, and the family rarely had insurance or much extra income to take care of their health.

“Growing up in my family, I thought not having access to healthcare, not seeing a doctor and juggling debt was normal,” Solis says. “I always took it as that’s the way it is. I didn’t know anything different.”

Solis says she was lucky to have her mother and other mentors pushing her to pursue scholarships and educational opportunities. It’s that advantage she wants to share with others.

“Breaking these barriers is not something that can be done alone because it takes harnessing everyone’s strengths and working collaboratively,” she says. “I’ve received so much help to be here, and I want to share that knowledge so others can pursue their career goals.”

But sometimes she still feels overcome by the support she’s been given. When asked about winning the outreach award, she says the best part was being nominated by her peers, Madison Bradley-Cronkwright and Allie Schrock. As she talks, she grabs a tissue and gently dabs her eyes.

“This year, I’ve grown to be more confident in myself and lean more into my own background, learning this is something I shouldn’t hide,” she says.

Solis says the recognition and interests from students and faculty in the talks has given her the confidence to know she is on the right path.

Alma Solis, right, after graduating with...