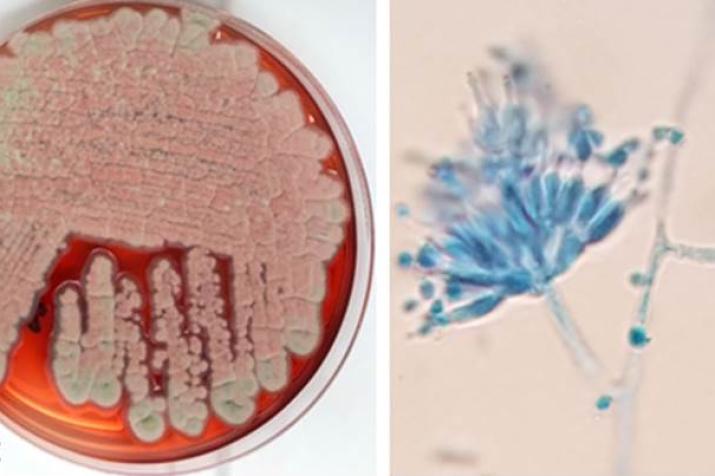

One of the two life stages of the fungus Talaromyces marneffei, which causes an opportunistic infection in people with compromised immune systems.

Published November 15, 2021, last updated on November 18, 2021 under Research News

When Thuy Le went to Vietnam in 2008 to conduct research on HIV drug resistance, what she saw in the country’s AIDS hospitals changed the course of her career.

About one in 10 patients she encountered were suffering from a mysterious infection she had never seen before. Most had dark, bumpy lesions on their face and arms, signaling a dangerous attack in their bodies. While the local doctors were familiar with the disease, there was no consensus and little medical guidance on how to treat it. And the disease was stunningly brutal, killing nearly a third of those it afflicted. Just diagnosing the infection took weeks, and sometimes patients died before the tests came back positive.

“I had never seen anything like it,” says Le, M.D., Ph.D., an associate professor of medicine, molecular genetics and microbiology and a faculty affiliate in the Duke Global Health Institute. “For a disease that common, and that kills one out of three people, to have no treatment studies was just unacceptable.”

The disease, known at the time as penicilliosis, is one Le now knows better than just about anyone in the world. She helped give it a new name – talaromycosis, to be in line with the fungus causing it, Talaromyces marneffei – and defied the first clinically tested treatment, which became the standard of care in 2019.

And now, after a decade of fighting to put talaromycosis on the medical and scientific agenda, Le wants to see the disease neglected.

But neglect, in this case, would be a good thing. Le is spearheading a campaign to have talaromycosis added to the World Health Organization’s official list of neglected tropical diseases (NTDs), which carries significant weight in shaping public health research and policy.

“Getting added to the NTD list would have a huge impact on this disease,” says Le. “It would raise awareness of the disease with funders and allow us to address its neglect very comprehensively.”

After a decade of fighting to put...

The Neglected of the Neglected

Created in 2005 to elevate the profile of infectious diseases that don’t receive much attention from funding agencies or private industry, the WHO’s NTD list comprises 20 lesser-known maladies, a diverse group that includes dengue, river blindness, schistosomiasis and guinea worm disease. Three fungal diseases were added in 2016, but talaromycosis has remained on the sidelines.

Le and Shanti Narayanasamy, M.B.B.S., a Duke infectious diseases fellow and global health master’s student, are quick to note the disease ticks all the boxes of an NTD. Found in tropical and subtropical regions of Southeast Asia, the fungal infection typically arises in patients with already compromised immune systems, and it often accompanies advanced stages of HIV infection. Around 17,000 cases are documented each year, leading to some 4,900 deaths.

And like other diseases on the WHO list, talaromycosis exacts its heaviest toll on the most vulnerable. The majority of those infected are poor and live in rural, mountainous areas with little access to robust healthcare. Pervasive stigma around HIV infection amplifies the social and economic isolation that can accompany infection.

“Talaromycosis is quintessentially a neglected disease,” says Narayanasamy, who authored an article, signed by more than two dozen researchers and policymakers from multiple countries, in the journal Lancet Global Health advocating its inclusion on the WHO list. “It’s really flown under the radar, which is why there are still so many fundamental questions about it.”

“It’s the neglected of the neglected,” adds Le.

Le has been working to change that. After encountering the disease in Vietnam, she completely overhauled her research, becoming one of only a few scientists in the world devoted to studying the disease. Before Le started working on it, the National Institutes of Health had funded just two projects related to talaromycosis ever. She has since earned four NIH awards and is working on a fifth.

Le’s research team published the first clinical trial on talaromycosis, which pointed to the anti-fungal drug amphotericin as a life-saving treatment. She has done some of the first epidemiological work on the disease, detailing the risks of infection among agricultural workers, and has developed new diagnostics being tested in parts of Vietnam, Myanmar, Thailand and southern China.

Still, Le dreams of more, starting with better therapies with fewer side effects and point-of-care diagnostics that could identify cases in rural areas. Not much is yet known about where the fungus harbors or what paths it uses to infect humans.

But with scant attention from funders and government policymakers, Le worries such progress won’t happen quickly enough. “You need money to identify new diagnostics and treatments,” she says.

Making a List

Landing a spot on the WHO NTD list could do a lot to bring talaromycosis out of the shadows. “If a disease is added to the list, it moves higher up the agenda for global, regional and national health policymakers, which could include greater funding for both disease control and research and development,” says Gavin Yamey, M.D., a professor of the practice of public policy and global health.

But Le and colleagues are targeting other lists, as well. They hope to get talaromycosis added to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s Tropical Disease Priority Review Voucher Program, which could help fast-track development of new anti-fungal drugs. The National Institutes of Health has recently added talaromycosis to its portfolio of NTDs, making it easier for scientists to seek agency funding for talaromycosis research.

In September, the team had another breakthrough, convincing the journal PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases to add talaromycosis and three other fungal diseases to its own roster of NTDs, which researchers (including DGHI’s Yamey) created as a more-inclusive alternative to the WHO list. Le describes it as “a big win for fungal diseases,” especially since inclusion on the PLOS list often presages a move by the WHO.

The next step is to lobby health ministers in affected countries to make a formal request to the WHO for the disease to be listed. “We think the timing is right and we have some momentum for change,” says Narayanasamy.

What particularly excites Narayanasamy is the prospect of luring more early-career researchers like herself into the field. An infectious diseases physician who came to Duke from Australia as a fellow with the Hubert-Yeargan Center for Global Health, she says more recognition from journals and funders can help assure young scientists that they will be able to earn grants and publish findings in high impact journals.

“If we’re able to get talaromycosis onto the NTD lists, we will be able to attract young researchers, both in the United States, but also in endemic countries,” she says. “We want people from Vietnam and other countries to see this as a research career, to see that their governments are putting money into this and will support their research.”

And if that happens, Le will have more allies in her quest to solve a disease so overlooked that it has to fight just to be neglected.

“When we do the right thing with effort and passion, we get people’s attention,” she says. “We want to build a community of clinicians, researchers, and policymakers who are committed to lift it out of neglect.”