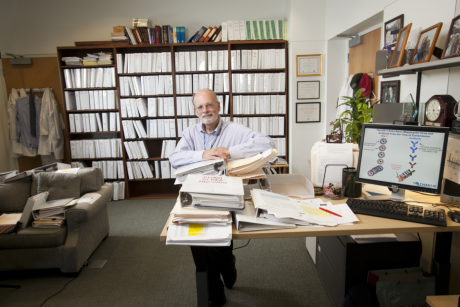

Tamara Fitzgerald, M.D., Ph.D., a pediatric surgeon and associate professor of surgery and global health, has been working in Uganda several times a year for more than a decade. Photo by Jjumba Martin

Published October 3, 2024, last updated on July 23, 2025 under Research News

This article first ran in the Fall 2024 issue of Duke Magazine and is reprinted with permission. See the original article

Rania Challita is shopping. Actually, “It’s more like a scavenger hunt,” she says. She’s going from shop to shop in the chaotic downtown market of Kampala, Uganda, with Patricia Atukuri, a biomedical engineering student at nearby Makerere University. They seek string, glue, paint as they navigate the maelstrom of cars, motorcycles, trucks. They’re gathering parts for one of the last pieces of a suite of tools that will expand laparoscopic surgery capacity in Uganda.

Another pair of students is off getting acrylic sheets laser cut. “If we were in the Pod,” Challita says – the Design Pod at Duke – “we could bring like five different sizes and see which one is best and print it out.” In Kampala, however, each trip takes hours. “You can prototype all you want in the states,” says Challita, a rising junior at Duke in biomedical engineering, “but it barely translates here.”

She’s part of a team from Duke’s Bass Connections interdisciplinary program that is here to learn that translation.

Paula Kworekwa and Sheillah Bagayana of...

Across Kampala, Dr. Tamara Fitzgerald makes a similar point on the road to a meeting when her driver slows to a halt in the kind of traffic jam that can last hours. To save gas, the driver turns off the car, cracking the windows, though that lets in smog and the omnipresent settling dust. “I sometimes wonder why something isn’t finished,” Fitzgerald says, thinking of communications with her Ugandan colleagues.

“And then I remember.”

The traffic jam clears and the driver drops Fitzgerald and her colleagues at the little building of ShiShi International, where hugs are exchanged, equipment unloaded and work begun on the assembly of the newest version of KeyScope, a laparoscope designed with African use – and manufacture – in mind. The ShiShi building is being renovated as a facility to build the laparoscope, a tube-like instrument with a tiny camera that is inserted through a small incision in the body to examine the interior of the abdomen and pelvis. Fitzgerald has been helping work on it for seven years.

Duke and Makerere students work on the box trainer on the porch of the Design Cube

Fitzgerald, pediatric surgeon and associate professor of surgery and global health, has been coming to Uganda several times a year for more than a decade. Her work here to build medical capacity has, among other things, helped create Uganda’s first pediatric surgical fellowship. She now only lightly checks in on that fellowship. “They don’t need me,” she says. Ugandan pediatric surgeons recently separated conjoined twins, she notes. “They’re perfectly capable of managing their own program.”

That is Fitzgerald’s ideal outcome: She provides helpful input, after which the Ugandan community does its own work. Fitzgerald helps build communities that solve their own problems. It’s called capacity building.

“I don’t try to change the world,” her students quote her saying. “I try to help other people change their worlds.” It sounds like the difference between offering a fish and teaching someone to fish, but Ann Saterbak, professor of the practice in the Duke Department of Biomedical Engineering, leads this Bass Connections project with Fitzgerald and says this is more than that. “It’s not even ‘teach to fish,’” Saterbak says. “It’s, ‘We need to get fish out of the lake.’” The goal is to combine everybody’s knowledge on how to do that.

Which is what brings Fitzgerald to ShiShi International. On her current Ugandan trip, she’s focusing on the laparoscope and a box trainer on which surgeons can practice using the device. It’s a small collapsible structure that stands in for an abdomen. Challita and Atukuri were looking for materials to hold it together.

Focusing on Local Needs

Uganda, like other low- and middle-income countries, is full of people who would love laparoscopic surgery, during which a surgeon inserts a laparoscope through a small hole to see into a patient’s body and uses other tools to perform surgical tasks. The benefits are many: smaller scars, faster recovery and fewer complications. But a laparoscopy suite at Duke runs around $200,000, with all the screens and electronics and equipment, to say nothing of maintenance or the tanks of CO2 needed to inflate patient abdomens during surgery. That’s not plausible in locations such as Uganda, where attempts to share laparoscopy tools have commonly involved groups providing nice metal laparoscopes, which must be sterilized in machines called autoclaves.

“A lot of hospitals in Africa,” Fitzgerald says, “don’t have autoclaves.” They don’t even always have reliable power. “The equipment was not really made for them. It was made for high-income countries.”

Enter the KeySuite, including the KeyScope and the KeyLoop, a low-cost metal framework that cheaply and safely lifts the skin of a patient to provide room for the surgery, removing the need for expensive and complicated CO2 canisters. For viewing screens, KeySuite uses a laptop, and the scope itself is plastic and waterproof: “You can dunk the whole thing in Cidex,” a disinfecting solution, to sterilize it, thus removing the need for an autoclave, says Jenna Mueller M.S.’13, Ph.D.’15, an associate professor of bioengineering at the University of Maryland who has been involved with KeySuite since she helped begin it as a postdoc in Fitzgerald’s lab.

The whole system should cost about $3,000. The cost is so low because, Fitzgerald says, the project uses “the human-centric design process,” a cycle that starts with long discussions with the people who will use the tool and never loses track of what they need. “We’ve basically designed laparoscopic surgery equipment for the needs and also the resources of Africa.”

Resources of all kinds. “The other thing we’ve tried to do in this project is intentionally design it so it can be built here in Uganda, with a company here,” Fitzgerald says. “That way it creates jobs. It creates a local biomedical infrastructure, and it makes a space where we’re trying to stretch the capacity here for regulatory approval and things like that.”

Enabling a local company to work its way through the maze of approvals in a new Ugandan industry is critical to the project’s success. Fitzgerald, Mueller and their compatriots want to help Ugandan biomedical engineers, students and workers change their world.

ShiShi co-founder and managing director Sheillah Bagayana says that is essential. “Even though we innovate, if there is no industry to take it from development to the market, you might as well never have developed it.” After she studied biomedical engineering at Makerere, she visited Western universities. “At MIT,” she says, “literally the venture capital is at the university.” Uganda lacked not only investors but companies for them to invest in. “Right then I said, ‘This is where the gap is.’”

It was a global surgery rotation in her final year of medical school that defined Fitzgerald’s future: “I came away from that trip thinking ‘I don’t know how I’m going to make this work in my career, but I know this is what I want to do.’” A mentor brought her to Uganda, where she began working on the pediatric surgical fellowship. She earned a Ph.D. in biomedical engineering along with her M.D. An introduction to Robert Ssekitoleko, the head of the biomedical engineering program at Makerere University, assured her continued work in the area. Ssekitoleko has become a linchpin of the work Fitzgerald does in Uganda. The two met when Ssekitoleko visited Duke in 2017. With that meeting, a million collaborations were born.

Ssekitoleko says Fitzgerald’s seeing things from both the medical and engineering perspectives “makes a very big difference.” Physicians “want this technology and [I] want it now,” he says, “without paying attention to the hurdles of getting that technology from idea to use.” Not Fitzgerald: “While she’s working in the hospital here she’s also able to see the gaps and then start having a go at solving those gaps using technology.”

Back at ShiShi, as Fitzgerald edits research papers emerging from this work, Mueller works with graduates of Ssekitoleko’s program to bridge those gaps, building the most recent generation of the KeyScope. They look forward to upcoming meetings, one where Ugandan surgeons will get a chance to test KeySuite tools and another with regulatory agencies, to try to move KeySuite into clinical trials. It has sailed through animal trials with surgeons at Duke. Clinical trials, on actual patients in Uganda, will be its last hurdle.

Many steps along the development of KeySuite have been Bass Connections projects, giving Duke students the opportunity to travel with and learn from Fitzgerald and her collaborators. Students address the current Bass Connections piece of KeySuite at the Makerere Design Cube, made of two shipping containers, which houses design tools. (A single-container version has been set up on the Duke campus.) Under the direction of surgical resident Dr. Shannon Barter, a group of Duke and Makerere students works on that box trainer. If African surgeons get laparoscopic equipment, they’ll need training. “The major challenge is you’re doing a three-dimensional task,” Barter says, “but you’re viewing it on a two-dimensional computer screen.” The low-cost, locally producible box trainer holds a series of tasks – move objects, tie knots – that surgeons must master for certification.

Presenting the KeySuite

The presentation to surgeons is a smash. It’s meant to begin at 8:30 a.m. in a small conference room in the Mulago Hospital Guest House. At 10 no surgeons have shown, so breakfast is served. “It’s just another presentation,” Mueller says, and Fitzgerald shrugs: “It’s Uganda. They’ll show up eventually.” They do. They listen eagerly to Fitzgerald and Mueller’s presentation and flock to the KeySuite. When someone asks about training, Barter sets up a box trainer and they flock to that, too. Applause erupts when someone completes a task.

Participants look beyond the surgical advantages and savings. Says Jamilla Nabukeera, a master of medicine in obstetrics and gynecology: “With this being done here locally, it will really boost the economy, the industry and supply,” offering not just Ugandan jobs and expertise but an easy supply of replacement parts. “I just hope that program is swift, whereby all the clinical trials are done so quickly, such that within a very short time we start using them.”

Before a group of Ugandan surgeons,...

The next day, in a larger conference room, Fitzgerald, Mueller and Ssekitoleko make a more-detailed presentation before tables of representatives from regulatory agencies. Concerned about human subjects, the panelists request many adjustments, but they are universally positive about the KeySuite, its cooperation among Ugandan and foreign partners and its capacity to make change. They suggest the changes they ask for can be made within months and clinical trials can begin. “The ball,” one panelist says, “is in your hands.”

After the meeting Kenneth Rubango M.S.’17 is ebullient. The director of biomedical engineering at Joint Medical Store, a Ugandan nonprofit medical supplies distributor, he sees KeySuite as not merely an improvement: “We see this as revolutionary.” KeySuite’s focus on what Ugandan surgeons need and will actually adopt will make the instrument not just useful but successful. Ssekitoleko notes that the group is pursuing international accreditation, making a device that will compete not just locally but internationally. “The surgeons, again, were saying, ‘We need this device, like, yesterday.’”

For Fitzgerald it’s another step forward. KeySuite is poised to make an enormous difference. She thinks back to her first days working in Africa: “When you help a patient at Duke, that feels really good, but you know that if you didn’t do it, somebody else would fill that space.” In Uganda, before the surgical fellowship, “if you didn’t do it, nobody else was going to, so you really made a big difference, and there’s no other feeling like that in the world.” With KeySuite, “I’m stepping back a bit from that individual helping, and we’re asking the question, ‘How can we help thousands or maybe millions of people?’”

The response – Ugandan developing Ugandan equipment that Ugandan companies will manufacture, distribute, and maintain to help Ugandan surgeons treat Ugandan patients – indicates they may have found a way.

“I think the best part about it is the reason why they flocked to it,” Fitzgerald says of the surgeons who have loved KeySuite. “There is an element of them that they know: This has been made for you. It hasn’t been made for somebody else; it was actually made for you.”