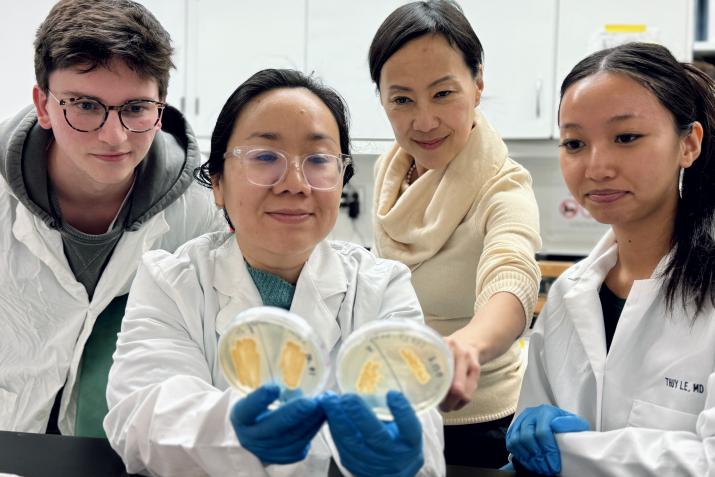

DGHI researcher Thuy Le, second from right, and her lab team refined tecnniques that significantly improve the speed and accuracy of diagnosis for talaromycosis, a rare fungal disease. Pictured from left are lab technician Matt Burke, lab manager Thu Nguyen, Le, and Aislinn Luong, a high school student working with Le’s team.

Published July 17, 2025 under Research News

Doctors who suspect a case of talaromycosis – a deadly fungal infection that is most commonly seen in patients with advanced AIDS – face an agonizing wait. Identifying the infection in a patient’s blood can take up to four weeks, by which time the disease may have progressed too far to treat. And even then, the diagnosis is frequently missed.

Such delays are not unusual with some fungal diseases, which are typically confirmed through a painstaking process of growing and isolating fungal cells from blood and other patient samples in a lab. But advances in molecular diagnostics could essentially erase the lag, delivering accurate diagnosis in a matter of hours, according to new research.

In the study, scientists at Duke University developed a diagnostic test that uses polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to detect traces of fungal DNA in a patient’s blood. Their method accurately identified 87 percent of previously confirmed cases of talaromycosis from stored blood samples, including nearly 60 percent of cases that had been missed by traditional blood cultures. The results were published in the April 2025 issue of the journal Medical Mycology.

“We have shown this PCR test to be more sensitive and much faster than a blood culture, yet it is also very specific to talaromycosis, such that the probability of a patient having talaromycosis who tests positive is nearly 100 percent,” says Thuy Le, M.D., Ph.D., an associate professor of medicine and global health at Duke who led the research. “with this disease, rapid diagnosis is extremely important, because it allows doctors to start treatment earlier, when treatment is most effective."

An Opportunistic Attack

Caused by exposure to the fungus Talaromyces marneffei, talaromycosis occurs predominantly in tropical regions of Southeast Asia, where its fungal culprit is endemic. As with many fungal diseases, it is an opportunistic infection, meaning exposure to the fungus may be harmless to most people, but can lead to life threatening illnesses among those with conditions that weaken their immune system, such as an HIV infection.

While infections are treatable, they are often not detected until late stages of the disease, when characteristic skin lesions develop. By this time, patients often have suffered serious damage to internal organs that cannot be reversed with treatment. About one in four patients dies from the infection, typically within one or two months of developing it.

Both speed and accuracy of diagnosis are critical to reducing that toll, says Le, who leads the National Institutes of Health-funded Tropical Medicine Research Center for Talaromycosis in Vietnam, where one in five people with advanced HIV disease develop the infection. Mortality climbs above 50 percent in cases where diagnosis is delayed, and it’s near 100 percent when it is missed completely.

One of the two life stages of the fungus...

Detecting Traces of DNA

Using PCR, scientists can create millions of copies of targeted segments of fungal DNA, making them easier to detect in blood samples. While a handful of PCR-based tests have been developed for talaromycosis, none had shown reliably strong accuracy, Le says. Her team was able to improve performance by tweaking several steps in the process of isolating and amplifying fungal DNA, including using microscopic beads to batter tough fungal cell walls so they release the DNA inside.

“It’s not rocket science, just a lot of diligent lab work to extract as much DNA as possible,” says Le. She notes that the sensitivity of PCR to mere traces of fungal DNA may allow it to detect infections even before symptoms arise, although this needs to be confirmed by future research.

Several hurdles remain before the test could be deployed widely in clinical settings, not the least of which is finding a commercial partner willing to invest in technology for a disease that affects only about 17,000 people each year. PCR also requires trained lab staff and centralized facilities, which may not make it ideal for use in the predominantly low- and middle-income countries where talaromycosis is prevalent, says Le. Her team is working with partners at the University of Hong Kong and a U.S.-based diagnostics company, IMMY, to develop a test that detects a protein secreted by the fungus, which is fast and simple enough to be completed at the point of care.

But the development of PCR testing marks meaningful progress on a disease that has received scant attention from researchers or funders. Le, who began studying talaromycosis as an infectious diseases fellow in 2008, when it was known as peniciliosis, led the first clinical trial on treatment of the disease in 2017, which established treatment guidelines that have helped reduce mortality by half.

Le led the first clinical trial on...

Emerging Fungal Threats

And with at least 200 species of fungi in nature that are known to be pathogenic in humans – many of which have not been studied by medical researchers – advances in talaromycosis may help spark innovation in an area of growing importance to global and public health. In 2022, the World Health Organization published its first list of priority fungal pathogens, citing an “unmet research and development need” to improve public health responses to emerging fungal threats.

In addition to Talaromyces marneffei, the WHO list includes fungal species such as Cryptococcus neoformans, which can cause pneumonia and meningitis in immunocompromised people, and Candida auris, an emerging threat that has caused outbreaks of drug-resistant fungal illnesses in health facilities in recent years. The report noted that hotter global temperatures may turbocharge the evolution and reach of pathogenic fungi, and increased resistance to antifungal medications, as well as the growing number of people living with autoimmune diseases and cancers who require immunosuppressive therapy, are also likely to increase risks of fungal diseases and outbreaks.

“What we are learning with talaromycosis can absolutely be applied to other fungal diseases,” says Le. “there are hundreds of fungal infections that are still really uncharted territory, and I am hoping this work can inspire more progress across the field.”

Le’s research in Vietnam has been funded by a National Institutes of Health grant, which launched a network of eight Tropical Medicine Research Centers in 2023 to advance treatment and in-country capacity for neglected diseases such as talaromycosis. While the future of that funding is uncertain, Le is undeterred, noting that virtually no funding existed for these diseases when she began her research.

“Over the past 15 years, we’ve made significant progress despite this being a disease that few people have heard of,” Le says. “We’ve been able to rally funders and others to help us make that progress, and I am hopeful we will weather this storm and see that work continue.”