Remember vaccine equity? In the pre-Omicron days of the pandemic, the alarming gap between vaccination rates in high- and low-income countries sparked widespread criticism and promises of action, including a pledge in September 2021 by U.S. President Joe Biden to send an additional 500 million COVID-19 vaccines to developing nations.

But with 2.8 billion people worldwide still not vaccinated against COVID-19, the problem has not gone away. In fact, as many countries begin to relax pandemic protections, it may be more urgent than ever, argues Gavin Yamey, M.D., a professor of public policy and global health and director of Duke’s Center for Policy Impact in Global Health.

In an article published today by the British Medical Journal (BMJ), Yamey joined global health experts from the U.S., Canada, Bangladesh, Peru and South Africa in urging renewed focus on increasing vaccine rates and access in low- and middle-income countries. The paper’s coauthors include Wenhui Mao, Ph.D., and Kaci Kennedy McDade from the Center for Policy Impact in Global Health, as well as Andrea Taylor and Krishna Udayakumar, M.D., from the Duke Global Health Innovation Center.

Yamey took a few minutes this week to discuss the article – and his worry that many people are prematurely thinking the pandemic is over. This transcript has been condensed and edited for clarity.

The BMJ article is titled, “it is not too late to achieve global COVID vaccine equity.” I was struck by that choice of phrase – not too late. Are you worried people have forgotten about vaccine equity?

Yamey: There is a concern amongst some scientists, including myself, that with Omicron receding in rich nations, a feeling that the pandemic is over has taken hold. There is also some rhetoric out there to suggest it's too late to do anything about vaccine inequity.

In our paper, we reject that notion that it's too late to achieve vaccine equity. There are around 2.8 billion people on this planet who have not had a single dose of COVID-19 vaccines. And we have to address that.

Just one in 10 people in low-income countries are fully vaccinated. We heard a lot about vaccine hoarding by rich countries as a major bottleneck in early stages of the pandemic. Is that still the case? Why is the gap still so large?

Yamey: There are many reasons, ranging from rich nations hoarding doses, rich nations being able to buy doses quicker, higher prices being charged to poorer nations, and low- and middle-income nations not being able to bargain for doses. It’s a whole range of factors.

The supply constraints are slowly improving. There have still been problems with, for example, donations of doses to low- and middle-income countries arriving very late, close to the expiration date of doses, which means that low- and middle-income countries actually have to trash those doses. So we aren't doing very well at timing the supply of doses to when countries need them.

You cite the examples of tuberculosis, malaria and HIV, which are relatively controlled in wealthier countries but have remained very dangerous in poorer parts of the world. Are you concerned we may see the same situation with COVID?

Yamey: One of the reasons why we wrote this paper is that we are worried that we're going to see a situation similar to what we have seen with those diseases. These are all diseases that were widespread everywhere in the world. Although rich countries largely controlled them, they continued to be endemic in low- and middle-income countries and kill a lot of people, particularly tuberculosis, which before COVID-19 was the world's number one infectious disease killer.

With billions of people in low- and middle-income countries still not vaccinated, we could see a very similar situation where the disease continues to wreak havoc in poorer nations, whereas the disease is well-controlled in richer nations, a giant global inequity that we have seen time and time again, once the rich world moves on and forgets about the pandemic.

The U.S. has delivered nearly a half billion doses so far and has pledged to give more than 1.1. billion by 2023. What is your response to people who say the U.S. is doing its share?

Yamey: All rich countries should be doing more, and should be doing it urgently, to expand global vaccinations. Yes, donations are a part of the puzzle. Certainly in the immediate term, we need more donations and we need them to be timed more effectively for when countries can use them. But donations are a charity model. They are a “crumbs from a rich person's table” model, and that’s not a long-term sustainable model, and it’s not equitable or just. What we actually need long-term is for low- and middle-income countries to be able to make COVID-19 vaccine doses for themselves -- a bottom-up model, if you like, rather than a top-down one.

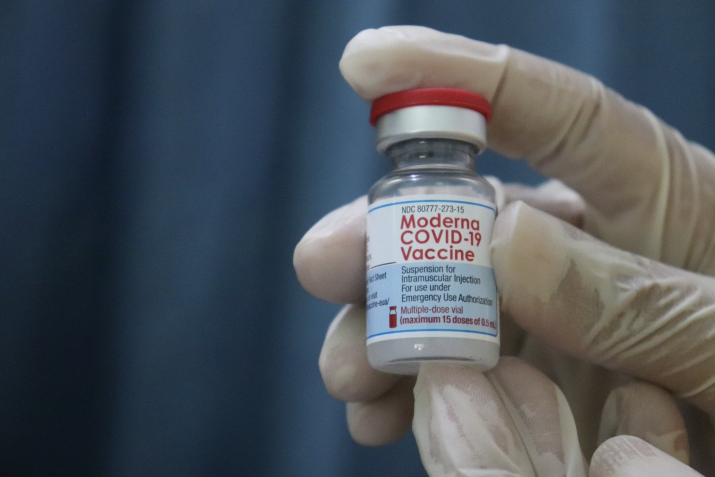

So what we really need is for the whole world to support globalized manufacturing of COVID-19 vaccines. And we are starting to see promising signs of that happening. In particular, the COVID-19 mRNA vaccine hub in South Africa, which has now promised to share mRNA vaccine technology with a number of countries in sub-Saharan Africa. We are starting to see deals, for example, between Moderna and the Kenyan government to make doses of the Moderna mRNA vaccine in Kenya. I am hopeful we are going to see more of these initiatives.

I think these initiatives also point to what I believe is going to be an absolutely critical trend in the future of global health, which is for regions themselves to acquire and manufacture their own doses. You see this with the African Vaccine Acquisition Trust, for example, which has been procuring vaccines for sub-Saharan Africa. And there are similar regional procurement mechanisms around the world. I think that's a trend that's here to stay.

The United Nations recently announced a deal that will allow companies to make generic versions of the Pfizer pills to treat COVID. Is that a positive sign for freeing up access to medications?

Yamey: It’s very good news. We’re not going to be able to eradicate COVID-19 any time soon, and so antiviral treatments, together with diagnostics and vaccines, are going to be critical to keep people from serious illness. If you can imagine a world in which everybody has access to those tools, you can see how we can turn COVID-19 into something akin to a cold or a mild flu. The Pfizer deal to be part of the U.N.’s Medicines Patent Pool is going to allow 92 low- and middle-income countries to have access to this drug. If that can be combined with diagnostics to get people diagnosed quickly, that's a real game changer.

And just imagine if the vaccine manufacturers had done the same. Imagine if they had said, "We're going to put the patent for these vaccines into the Medicines Patent Pool so the whole world can make these vaccines." We wouldn't have the global vaccine inequities we are today.

Weren’t programs like COVAX envisioned to prevent the kind of vaccine nationalism we’ve seen? Was COVAX a failure?

Yamey: The idea behind COVAX was the right one. I think it was a beautiful vision of a world in which every country would come together and buy vaccines through a buyer's pool and ensure that elderly people, health workers and medically vulnerable people everywhere on Earth would get vaccinated first.

The idea was that if everybody came to COVAX to buy doses, then there would be a large amount of upfront money available that could have funded research and development. With the whole world buying. COVAX would've had amazing bargaining power with the companies to get low prices.

Unfortunately, there was a vaccine grab. Three dozen countries went outside of COVAX and went directly to vaccine makers and said, "Give us all the doses you can." They bought billions of doses up front, before vaccines were even made, before they were even licensed. And that left COVAX at the back of the queue. There just weren't doses for COVAX to buy.

COVAX, of course, has made some of its own missteps and some of the problems were of its own making. Independent examinations of COVAX have shown that. They weren't very good, for example, at consulting with low- and middle-income countries during the design phase or consulting with civil society. They didn't do well to raise money at the beginning to compete against rich nations to buy doses. But in my view, as an observer of what happened, the main problem that got in the way of COVAX's success was the hoarding of doses by rich nations. No doubt about that.

The other part of COVAX is a traditional charity model. COVAX has raised money from donors, governments and foundations, and through that more traditional mechanism, it has managed to vaccinate over a billion people now in low- and middle-income countries. So I think we have to acknowledge that the counterfactual to COVAX is no COVAX. It has also had its successes.

In the BMJ article, you and the other authors warn about the danger of thinking the pandemic is over. Do you think the recent decline in case numbers in the U.S. has created a premature sense of relief?

Yamey: This virus has shown us, over and over again, that when new variants arise, COVID-19 can be disastrous again. And we have seen new variants of concern arise when SARS-CoV-2 is passing in an uncontrolled way through largely unvaccinated populations. The most effective way that we can prevent further variants of concern from arising is to vaccinate the world.

We are also concerned because we think it's deeply unethical to think that rich people deserve the protection of being fully vaccinated, but low- and middle-income countries don't. That's just a profoundly problematic inequity.

But it’s also incredibly shortsighted for rich nations to think we should just move on now and not help to vaccinate the world. We know that when the virus continues to pass in an uncontrolled way through low- and middle-income countries, it’s dreadful to the economies not just of those countries, but of rich countries, as well. One study suggests that when rich nations are highly vaccinated and low- and middle-income nations are not, about half of the economic costs are still felt by rich countries through things like disruption of supply chains and reduced exports to low- and middle-income countries.

But the best reason to stay focused on this issue is that we could save a huge number of lives. One recent study suggested that if we were to vaccinate everybody in low- and lower-middle income countries with three doses of an mRNA vaccine, we could save up to 1.5 million lives. So we can’t just say it’s time to move on and think about other things. Other nations, low- and middle-income nations, don't have that luxury of moving on.

In the past, you’ve written about cycles of panic and neglect, where societies mobilize to fight an active pandemic but then relax once the pandemic subsides, only to see the disease return. Could that happen with COVID?

Yamey: Our group here at Duke studied this empirically, and we know that this happens. We saw, for example, that funding for pandemic preparedness and response rose after the Ebola epidemic in West Africa in 2014-2016, and then it fell again once that epidemic receded.

Many of us thought since COVID-19 has been so devastating to every nation that surely this time we won’t repeat that cycle. But there are already suggestions that this might happen again. Look at what’s happening in the U.S., with Congress is already cutting off funding for the kinds of preparations that are necessary to respond to a new surge. We need to do better at surveillance so we can understand when and where a new wave is arising. We need to have tools in place at the ready everywhere, rapid testing, antivirals, high-filtration masks, like N95 masks. We need to have the ability to get people quickly diagnosed and treated. There’s a whole host of things that we need to be doing, not just to guard against a new surge of COVID-19, but to prepare for future pandemics. It is far better to be prepared than it is to panic.