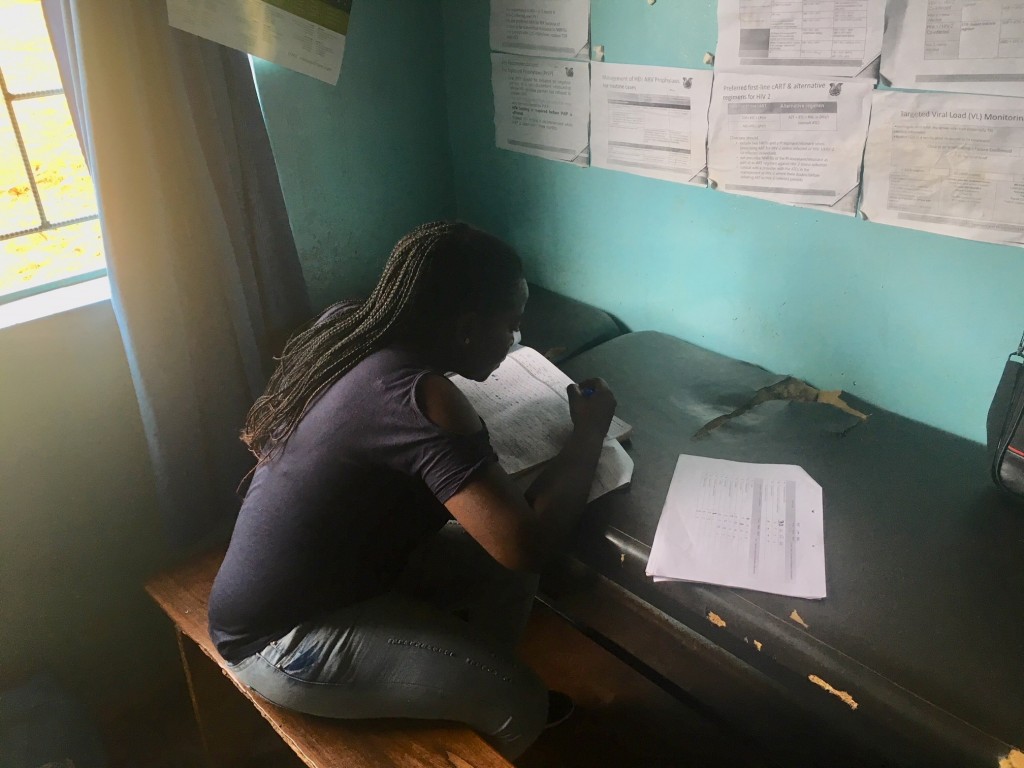

The Maternal and Child Health Coordinator at Petauke District Health Office arrives at a rural health center to collect data.

Published February 9, 2018 under Voices of DGHI

By Brittney Wittenbrink, MSc-GH ‘16

Brittney Wittenbrink, a 2016 graduate of our Master of Science in Global Health program, began service as a Peace Corps Response Volunteer. She’s working as a Maternal Health Implementer for Saving Mothers, Giving Life (SMGL) with the goal of reducing maternal and newborn mortality in Petauke, Zambia. Brittney is keeping a blog—BrittWitt Abroad—to chronicle her experiences, and from time to time, we’ll be featuring posts from her blog. Here’s her latest post (from February 2):

Last week it felt like I ventured to the ends of the earth to collect data. It was really just the boundaries of my district, but in rural Zambia it feels like one in the same.

Part of my job is data collection and management. I work at a district health office and normally collect monthly reports from the 47 facilities in my district. They are slow to trickle into my office and I usually only chase after them if I’m already visiting a facility for another reason.

However, last week an important quarterly reporting form was due for SM360—the NGO I technically work under. They are serious about data collection and sent a Monitoring and Evaluation Officer to Petauke for a full week to collect the forms all the facilities.

Only 29 of the 47 facilities turned them in before her arrival, which was apparently a big improvement from last quarter. The plan was to drive to each of the eighteen facilities with missing forms to either collect them or use their registers to fill them out ourselves.

We set off on a five-day land cruiser trek across the district with Idah, the M&E Officer; Maureen, a nurse from the district hospital; Michael, a SM360 driver; and myself. Royce, my supervisor, joined us the final day.

Each day we’d drive the entire day, visit a few facilities, return home to sleep, then venture out a new direction the following day. It was a long, exhausting and exciting week.

Typical rural health facility in Petauke district

Chibale Health Post—4 hours from Petauke Boma

The journey brought me to parts of my district that are unimaginably rural. One facility we visited was a four hour drive from the boma (Zambian word for town or urban center). We passed more villages than I knew existed; in each one, all the villagers emerged to investigate the sound of our approaching vehicle. Transportation is not easily accessible in these areas and a car passing through is not a common occurrence.

Between the villages were fields and fields of maize. This rainy season has been devastatingly dry so far and the rains fall sporadically. Some fields were lush and green while others just down the road were dry and brown. We passed one tiny village with dry maize fields on both sides and Maureen solemnly declared, “There is hunger here.” I am worried how these rural parts of my district will fare if the drought continues.

Past Petauke boma’s nice paved roads, the roads quickly turned to rocky dirt paths riddled with potholes, herds of animals, and dilapidated bridges. Some sections were calm while others were so steep and rocky, I wasn’t sure the Land Cruiser could scale them.

The long travel times are due to road conditions more than distance. Sometimes the driving slowed to such a bumpy crawl that my step counter was tricked into thinking I was running instead of riding in a car! On the day I was in the car the longest, maybe 10 hours, I clocked over 21,000 steps just from being tossed around inside the land cruiser!

Many of the roads are unpassable during the rainy season when the tiny bridges become overwhelmed (and often destroyed) by streams turned into raging rivers. To travel, people are either forced to take exceedingly long alternate routes or just wait for the water to recede.

View from the car

This decision fell to us one day as well. After traveling to one of the more rural facilities in the morning, a sudden, intense, rainstorm nearly stranded us when we tried to return home that afternoon. We came upon a bridge with water rushing over it (the stream was bone-dry earlier in the day) and a large group of people patiently waiting to cross.

Several men were charging a few kwatcha to help others across—they’d even carry you on their back for a few extra! Michael was convinced we could drive across, but I was not. I’m from Houston, Texas, where they indoctrinate us with, “Turn around, don’t drown,” thanks to the frequently flooded streets that are known to sweep away cars; driving into raging water goes against my Texan survival instincts. He won, though, and we piled in the land cruiser and inched across.

Being the only one that could swim, I was mentally figuring out which order I would have to save them in if we tipped over. We made it about three-quarters of the way across and stopped. Michael revved the engine, but the car remained frozen with water rushing all around it.

For a second, I died internally trying to figure out if we could get off the bridge before the water pushed us off. Then he started cracking up and continued driving. ARGHHHH are you kidding me?! Honestly, it was a really great practical joke—he definitely got us!

Flooded road

My team (from left): me, Idah, Michael and Maureen

The roads are also full of animals! Because cars don’t pass frequently, there are goats, dogs and pigs lounging in the sun that always seem to scramble out of the way in the nick of time. Chickens dart across at will. Huge herds of grazing cows wander into the road as well.

There are no fenced-in pastures, so the cows have to be led around to find food and water. This job falls to small boys whacking their herds with sticks to corral them. The boys in very rural areas often look after cows instead of going to school; a few manage to do both. Usually, if they look after them for three years, they are given one of their own. Some of the boys appear to be teenagers but most look shockingly young, sometimes even five or six years old.

Other than the typical village animals, we were close enough to a national park at one point to see some more exciting animals; I was hoping for elephants! A family of baboons ended up being the coolest thing we spotted, though.

The only scary animal encounter was the swarm of tsetse flies that suddenly overwhelmed the vehicle. Tsetse flies have painful bites and can carry trypanosomiasis (African sleeping sickness), so they should definitely be avoided. We frantically rolled up all the land cruiser windows, hugged ourselves as we checked for any rogue flies inside the vehicle, then watched dozens land on the windows as we drove through the bush. Whew.

The data collection itself was interesting. Some reports were complete when we arrived—the facility was just unable to bring them to the boma. Others hadn’t been started, leaving us to pore over their registers and complete them ourselves.

We asked about the maternal deaths and complications and documented the causes. We did data audits and compared the forms with registers to check them for accuracy as well. We caught a couple facilities filling out the forms carelessly or obviously making up numbers. One facility reported 31 stillbirths, but after checking, we corrected it to the real number: two (31 in one quarter would have the Ministry of Health, the CDC, and a dozen other organizations descending on that facility in hazmat gear!).

We also checked that each facility had a handwashing station set up and used it frequently because of the country’s current Cholera outbreak. So far our district doesn’t have any confirmed cases, but Lusaka has thousands!

Idah checking a form—sometimes hospital beds double as desks

I also saw some fascinating but painful medical cases. In one facility, we were touring the labor ward and asked a mother who had given birth an hour or so ago how she was feeling. She responded that she was bleeding.

Maureen quickly moved her to an examination bed and opened her legs; blood was rushing out. It was a post-partum hemorrhage—a leading cause of maternal death. She expertly stopped the bleeding and stitched up a perineal tear. I’m not sure what would have happened if we did not arrive at that moment. The facility’s midwife was out and the staff that delivered her were not trained birth attendants—they were environmental technicians. The district tries to ensure a skilled birth attendant is at every delivery, but unfortunately, it does not always happen. Thankfully, it all worked out.

At another facility, I looked on as Maureen examined a recent stillbirth. It was heartbreaking. The baby boy had only died a few days before birth; he was large with a full head of dark, curly hair. The mother had contracted malaria recently, and they believe the baby did not survive her high fever. She sat in the corner stoically; it wasn’t necessarily sadness, but a look of defeat etched on her face. These things happen; in rural Zambia, baby showers and baby names come weeks after birth, not before.

I saw countless other medical cases as well. Some were also devastating, like a baby boy with advanced HIV who I’m not sure will ever leave my mind. But most were positive and showed promising signs that interventions were working. The nurses stopped to help with a vaccine campaign, where more than 100 children were vaccinated against preventable diseases. Three women received birth control implants in their arms because they knew their family planning options and wanted to space out their pregnancies. A facility performed a successful C-Section right before we arrived and we saw the mother and baby resting well.

I have seen all these maternal health indicators on forms and in registers countless times, but they were just numbers. It is humbling to see the cases, and the people, behind them.

Royce and Maureen vaccinating a long line of babies

Overall, I had an amazing week. Venturing out to collect data led to so many incredible experiences throughout the rural areas of my district. Plus, the group I traveled with was so much fun! I can’t wait to do it again next quarter!

I also wanted to try something new and threw together a video of some of my clips from the road! It fun to make, and I hope you like it! Check it out below!