An interviewer conducts household survey in rural El Salvador for a Center for Health Policy and Inequalities Research study. Photo by Hy V. Huynh.

Published March 12, 2018 under Research News

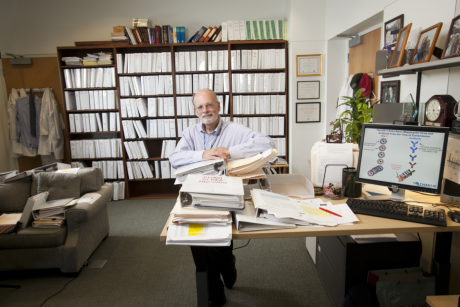

In qualitative research, in-depth interviews can be an immensely helpful investigative tool. However, the nuances of one-on-one interviewing can sometimes make it difficult to obtain useful results. Rae Jean Proeschold-Bell, associate research professor and founding director of the Evidence Lab at the Duke Global Health Institute, frequently integrates qualitative interviews into her research. In this article, she shares five interviewing tips that have served her well.

1. Convey Intent

Proeschold-Bell says it’s important for the interviewer to know the intent behind each question so that it can be clearly conveyed to the interviewee. Understanding the intent of a question, she’s found, helps interviewers decide whether or not the participant has fully answered the question. This way, they can ask follow-up questions and not leave gaps at the time of data collection. Proeschold-Bell recommends writing the intent of each question below it in italics on the interview script.

Proeschold-Bell also suggests a few more subtle techniques for helping interviewees understand what is really being asked and soliciting pertinent and thorough responses. Asking the question in several different ways can help clarify its meaning. Follow-up prompts such as “That’s really helpful; tell me more about that,” or “Can you describe what was unpleasant about it?” can also give interviewees helpful guidance in crafting their responses.

“You can also convey intent by explaining more broadly why you’re doing the research, so interviewees will be more likely to give you relevant information,” Proeschold-Bell said.

2. Don’t Sway the Participants

Acquiescence bias, which occurs when interviewees agree with what they think the interviewer wants to hear instead of giving their unbiased answer, can often prevent interviewees from sharing all relevant information. Research from Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research shows that when power dynamics are present in an interview, it may be especially difficult for an interviewee to give an honest answer.

To minimize acquiescence bias, interviewers can emphasize that the participant is the expert in the subject matter of the interview. For example, they can start the interview by saying, “I’ve asked you to talk with me today because you are an expert in what it’s like to be a patient in Eldoret.”

Interviewers should also avoid nodding or other body language that expresses agreement with the participant. Instead, interviewers should say, “That’s very helpful,” or “Thank you for those thoughts.” Otherwise, participants might elaborate on a point that isn’t actually very important to them just because the interviewer seemed to agree.

Proeschold-Bell also recommends that interviewers pay attention to—and record—interviewees’ non-verbal responses, which often communicate feelings and attitudes that the verbal response doesn’t capture.

3. Eliminate Interviewer Bias

Proeschold-Bell says it’s critically important to eliminate interviewer bias through the interview process. Knowing the interview guide extremely well helps an interviewer pace the interview to avoid running out of time, and adhering to the scripted wording for each question helps maintain unbiased prompting across all interviews. Additionally, if an interviewee starts answering a question that is going to be asked later, the interviewer can ask them to wait.

It’s best to ask interview questions in a specific order because covering certain questions first may influence how interviewees think during later questions. Finally, she recommends, “Ask all questions of all respondents, even if you think you know what they’ll say. They will surprise you sometimes!”

4. Consider a “Test Run” Period

Proeschold-Bell sees her first several interviews for a study as pilots. Learning from these first few test runs and improving questions and interview techniques for future interviews can have a significant impact on the quality of the study. This means that data quality from the first few interviews may not be as strong since some of the questions change, but the data from the interviews later on will be more useful. Proeschold-Bell recommends numbering interviews chronologically to link interviews to the phase of development in which they were conducted.

5. Make Time for Post-Interview Reflection

After an interview, Proeschold-Bell recommends immediately reviewing the data. “This helps capture good ideas that may otherwise be forgotten,” she says. In fact, she suggests creating a review form with a few open-ended questions that can help capture strong reactions and flag questions that didn’t work well or questions that should be added.

It’s also helpful, she says, to note responses that were different from those given in previous interviews. Doing this may generate ideas to analyze more carefully later on.

Looking for more research design tools? Check out Proeschold-Bell’s recent article, “Five Tips for Designing an Effective Survey.”

Proeschold-Bell recommends that interviewers pay attention to—and record—interviewees’ non-verbal responses, which often communicate feelings and attitudes that the verbal response doesn’t capture.