Published December 21, 2022, last updated on December 3, 2024 under Research News

Jason Villegas, pastor at Murfreesboro...

Jason Villegas first felt called to the ministry when he was 17. But a few years after graduating from Duke Divinity School in 2013, he was feeling the strain of his chosen path.

He had served as a pastor at several Methodist churches in North Carolina, trying to use his identity as a young Latino to bridge cultures and generations in the mostly rural communities. But after nine years of pastoral work, he still had not been ordained as a minister. He was told he wasn’t “Methodist enough.”

“The cross-cultural and racial pushback caused my anxiety and depression,” says Villegas, who was finally ordained in 2021. Sometimes, he relied on bad habits to cope. “I played computer games longer than what I should have, and I ate as a way to numb myself.”

In 2020, Villegas found a more productive way to deal with the stress. He enrolled in the Selah Stress Management Intervention, a study run by the Duke Clergy Health Initiative to help church leaders manage the physical and mental load of their jobs. He learned mindfulness techniques, practicing at home and in the sanctuary of his church, Murfreesboro United Methodist, before sermons. Now, he rarely needs to take medication for anxiety.

“This multi-pronged approach has changed my relationship with stress,” he says. “As that changes, your brain starts to rewire itself instead of being taken over by stress.”

Getting Off the Hamster Wheel

Faith leaders are often the first to come to the aid of those in their communities, lending comfort and emotional support to those in crisis. But often, such caregiving comes at the expense of their own health, says Rae Jean Proeschold-Bell, a professor of global health and a co-principal investigator of the Clergy Health Initiative.

The COVID-19 pandemic only amplified the pressure, with clergy often stuck in the middle of conflicts within their congregations about masking and lockdowns. When researchers surveyed a group of North Carolina clergy prior to the study’s start, 71 percent said they often felt stress stemming from public criticism, conflict or more areas.

“We know stress harms your mental and physical health, and can even lead to death,” Proeschold-Bell says. “With the Selah study, we sought to identify small effective practices that can fit into a busy professional’s life and be appealing to people who are called to their work.”

Launched in April 2020, the study randomly assigned participants, all clergy in the United Methodist Church of North Carolina, to learn one of three stress reduction practices; why Proeschold-Bell and her team chose those interventions for the study are explained in a paper published Dec. 2021. (For a description of the practices, see at the end of this article). Researchers expect to release the full results in early 2023, but preliminary data show that practices reduced symptoms of stress.

“The fact the reduction was consistent across all three interventions tells me people are willing to do something about their stress if what to do is clear enough,” says Proeschold-Bell, who studies the effect of positive emotions on physical and mental health. “They want to feel better. These small practices make a big difference.”

Shannon Marie Berry, the pastor at...

Shannon Marie Berry, who leads a United Methodist church in Fremont, N.C., says the Selah study came at the perfect time. She suffered sleepless nights and lived in a fight-or-flight state before using mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR).

“MBSR got me off the hamster wheel I couldn’t get off of by myself,” she says. “It gave me permission to remember I deserve the opportunity to care for my own self. When you are in a helping position and not taking the time to fill yourself, it means you have nothing to give any individual. We can’t be that way.”

Berry says the pandemic tested her in ways she couldn’t foresee. Her grandmother died in 2020, and Berry led an online memorial service for her. Just a week later, one of her congregants, a woman in her 70s, passed away, leaving Berry with the tough decision about whether to hold a service in the church. She opted for a socially distanced memorial outside. While she knows she made the right decision, she still feels guilt.

“I know it was circumstances beyond my control, but [during the pandemic] you had to make decisions you could sleep with at night – alone,” says Berry, as she wipes tears from under her eyelashes. “I spent hours sitting on the front stoop of my house that faces the church, crying out of hopelessness, helplessness and feeling overwhelmed.”

Finding Daily Gratitude

The competing demands of serving a congregation, says veteran pastor Michael Kurtz, can feel like being a dog at a whistle convention.

“You have this voice over here, one over there, and you drive yourself crazy,” says Kurtz, who retired in June after 40 years of pastoring. “You don’t end up serving the church because you’re so scattered. You’re not focused on the call.”

In the Selah study, Kurtz used a prayer-based practice called the Daily Examen. Every morning, he would review the previous day to find things for which he was grateful. The exercise helped him cope with the stress of seeing his daughter go through a divorce.

“It gives oneself permission to pause, come apart, and embrace the pause,” he says. “Finding God in the situation didn’t come quickly and it takes work.”

Participants in the study didn’t just see improvements in mental health. Some clergy wore devices to monitor their heart rate during the study.

Michael Kurtz, a retired Methodist pastor, takes a break from hiking at Sunset Overlook in North Carolina's high country. He practiced The Daily Examen as part of the Selah study.

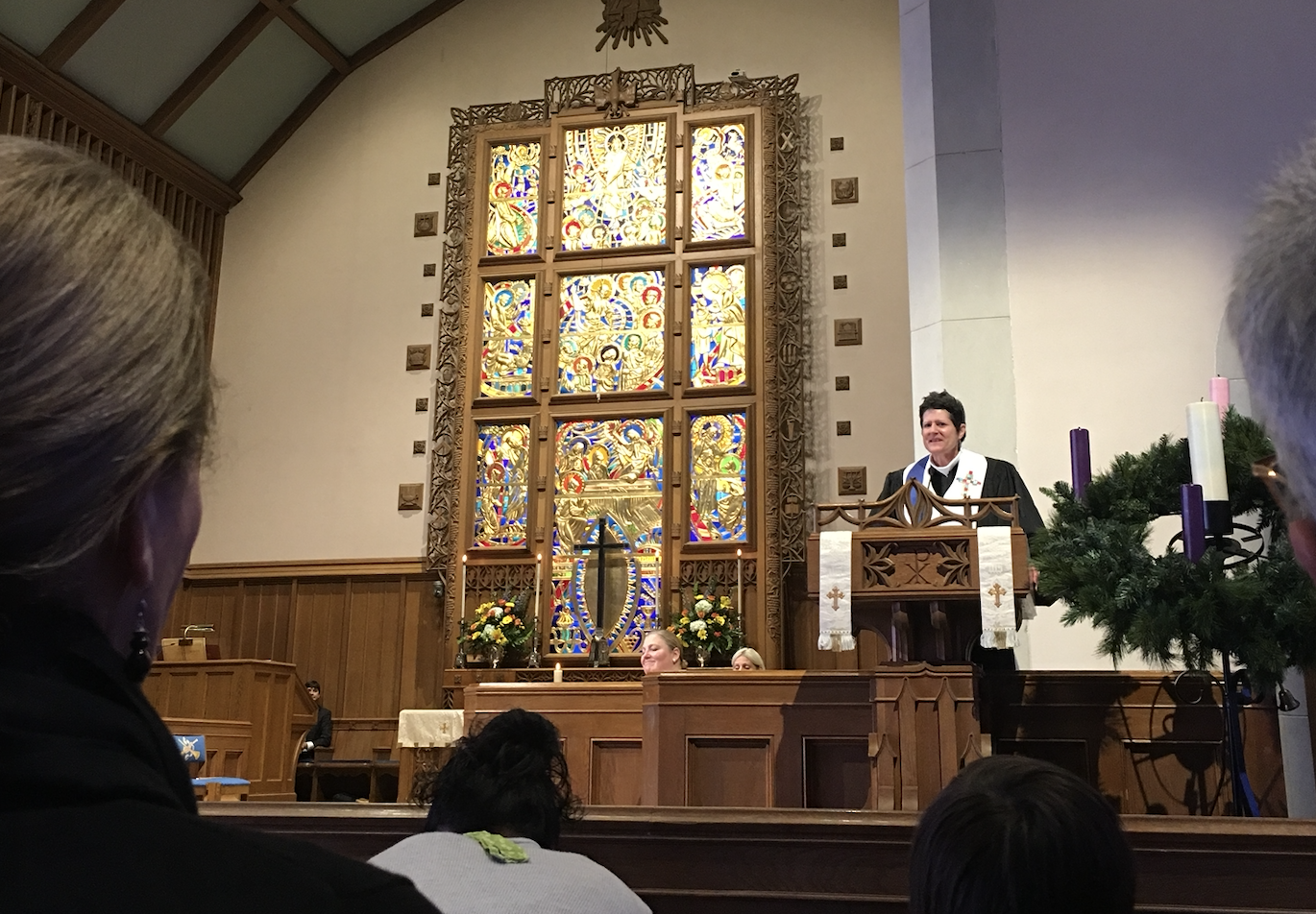

Kurtz leading a worship service.

“One unique thing about our study was measuring heart rate variability, or HRV for short. Improvements in HRV are related to reduced risk for cardiovascular disease,” says David Eagle, assistant research professor of global health also at DGHI, who led the bio-physical study data. “MBSR resulted in a 14 percent improvement in HRV.”

Jessie Larkins, a Methodist pastor who served as the Selah project director, says those results show stress reduction can change pastors’ lives for the better.

“The system in which [clergy] work is broken, and we need to advocate for changes for the sake of clergy well-being,” she says. “One thing I take away from this study is we can help you cope and thrive while doing God’s work in a complicated system.”

Feeling the Tension Lift

For Laura Hamrick, the demands of 17 years in the parish ministry were so great that when she was diagnosed with lymphoma six years ago, it almost came as a relief. Taking leave from her church for treatment “felt like a spiritual retreat,” she says.

Now in remission, Hamrick has joined the Clergy Health Initiative as its clergy engagement coordinator. Funded by The Duke Endowment and housed jointly in the Duke Divinity School and DGHI, the program has been working for more than a decade to promote health and wellbeing among United Methodist church leaders.

Before joining the research team, Hamrick participated in the Selah study, creating a corner in her Charlotte home dedicated to journaling, meditation and breathing awareness. She practiced yoga, often with her two cats clinging to her, and sat for moments of quiet reflection in what her 17-year-old son calls the “prayer chair.”

Laura Hamrick prays as she participates in the Selah study. She also journals and practices yoga, which are part of the Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction intervention.

Laura Hamrick prays as she participates in the Selah study. She also journals and practices yoga, which are part of the Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction intervention.

Hamrick speaks at her uncle's funeral inside Myers Park Presbyterian Church in Charlotte on Dec. 13, 2017.

Hamrick speaks at her uncle's funeral inside Myers Park Presbyterian Church in Charlotte on Dec. 13, 2017.

“Very quickly, and physically, I could feel the tension leave my body,” she says. “As I first experienced this, it was unexpected. I would often cry during that time.”

During the study, clergy received text messages to offer reminders and check on progress. Proeschold-Bell says roughly 70 percent of participants practiced the interventions on any given day for six months. And while the study ended in October 2021, many, like Hamrick, still use the techniques.

That encourages Proeschold-Bell, who says clergy sometimes feel like taking care of themselves takes time away from their service to the community. “We wanted to bring clergy together and create a culture and atmosphere that gives permission to attend to your physical and mental health,” she says.

“That’s exactly why I was here,” says Villegas, who says he is calmer and deals with conflict better since participating in the study. “I don’t want stress to hijack my body. I want to be able to observe and recognize it, greet it and work with it. There’s no way anyone in church work can survive without practices like this that help regulate the mood and nervous system.”

(You can read a pre-print publication of the Selah study that has not yet been peer-reviewed here).

The Selah Stress Management Interventions

The Daily Examen

This structured prayer practice was used by St. Ignatius of Loyola 500 years ago and has been practiced ever since. The routine takes about 15 minutes each day and includes five steps: become aware of God’s presence, review the day with gratitude, pay attention to emotions, choose one feature of the day to pray about, and look forward to tomorrow.

Stress Proofing

This technique uses a combination of exercise, body awareness and lifestyle changes to better understand stress biology and symptoms. Participants did breathing, walking and stretching exercises and lifestyle changes such as less device use at night to promote sleep.

Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction

This practice involves techniques such as breath awareness, meditative walks and a practice called Loving Kindness Meditation, all of which have been shown in other studies to reduce symptoms of anxiety and stress.