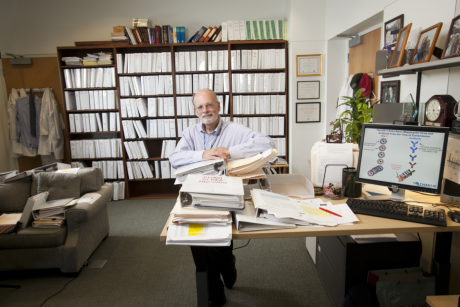

Patrick O'Meara making dry ice from scratch in order to keep Wendy Prudhomme O'Meara's lab materials cool during a 2-day trip to Kenya.

Published November 17, 2020, last updated on May 5, 2022 under Around DGHI

Every year, Wendy Prudhomme O’Meara and her family travel from Eldoret, Kenya, to Durham, North Carolina, to visit family and colleagues at Duke. Prudhomme O’Meara, associate director for research at the Duke Global Health Institute, lives in the Rift Valley region in western Kenya, where she spends much of her time studying malaria.

Recently, when she and her husband Patrick and their two kids prepared for their two-day return trip back to Eldoret, they made plans for an overnight stay in Nairobi, Kenya. But what was supposed to be a routine journey home took a turn for the worse when Wendy's lab materials faced risk. The challenge, though, became an opportunity to use their resourcefulness and creativity — qualities that come in handy when you work in global health, Wendy says.

The trip from the US to Kenya takes a long time, Patrick says, explaining that this time around they were traveling with important reagents needed for Wendy’s lab in Kenya. Rather than having them shipped and potentially arriving months later, they planned to carry the reagents themselves and keep them cool on dry ice for the 29-plus hour trip to Nairobi. Once there, they could then repack the cooler again before the final daylong leg of the journey to Eldoret.

Dry ice is solid frozen carbon dioxide and needs to remain within a sealed cooler in order to keep from evaporating, says Patrick, a mechanical engineer and “all-around fixer” according to Wendy. So, the morning of their departure, Wendy picked up the cooler filled with the reagents and dry ice that had been prepared by her colleagues at Duke and they set off for Nairobi.

“As soon as we got to the hotel [in Nairobi], we knew we needed to repack the cooler before the dry ice evaporated into gas essentially, and once it’s all gone, there’s no more cold to keep the reagents cold and the precious cargo could start to deteriorate,” Patrick explains.

Wendy Prudhomme O'Meara, associate...

Wendy had arranged for colleagues in Nairobi to acquire dry ice and have it waiting for them upon arrival. There was one glitch, though. The box used to transport the dry ice was not the standard dry ice cold box — it was more like a picnic cooler.

“So, when we opened up the cooler to look at the dry ice, the bag was empty,” Patrick says. It had completely evaporated into carbon dioxide.

Still many hours away from their final destination in Eldoret, the Prudhomme O’Mearas made desperate attempts to locate dry ice locally in Nairobi. But it was a Saturday evening and most places were closed and would remain closed on the following Sunday.

Patrick turned to the internet for an alternative solution to their problem and discovered that they could make their own dry ice using a carbon dioxide fire extinguisher and a pillowcase.

“As with a lot of things in Kenya, you kind of have to solve problems yourself,” Patrick says. “You can’t just call an expert or run down to Home Depot and pick something up. You learn to solve problems and adapt to the resources you have available.”

With help from the hotel staff, some welding gloves, and a pair of sunglasses in lieu of safety goggles, Patrick was able to safely replace the dry ice in the cooler.

“We had quite an audience of hotel staff gather around in the parking lot to see what these crazy folks were going to do with an industrial-size C02 fire extinguisher,” says Wendy.

“In the end, you can figure it out,” Patrick says, noting that they were able to successfully deliver the reagents to Wendy’s lab.

"It doesn’t matter how much planning you put into something, like organizing dry ice delivery to a hotel in Nairobi weeks in advance, you always have to be ready to be creative and think outside the box. You can never anticipate the challenges that will actually arise," Wendy says. "This is part of what I love about working in global health. The challenges today will never be the same as the challenges yesterday and you never know what will happen tomorrow."

While the trip back turned out to be a little rocky this time around, the Prudhomme O’Mearas wouldn’t have it any other way. Together, with their 6-year-old son and 4-year-old daughter, they’ve made a life they love in Kenya.

“These are our friends, our family, and this is our home,” says Patrick.