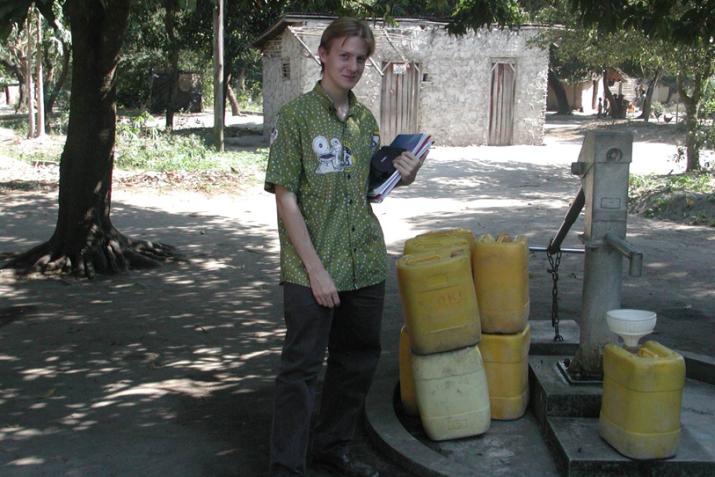

Marc Jeuland stands in front of a hand water pump in Mozambique.

Published August 27, 2019, last updated on April 7, 2020

Early in his career, Marc Jeuland learned a couple of important lessons about public-health interventions that, while obvious in theory, he believes are too often overlooked in practice:

There’s no silver bullet. And context matters.

Jeuland is an environmental economist with appointments in both the Duke Global Health Institute and the Sanford School of Public Policy. His primary fields of study are water, sanitation and energy, and his overarching ambition is to contribute to the development of more sustainable interventions through better evaluation of policy and systems.

“I think the international community–and, oftentimes, the public-health community–likes to look for silver-bullet, one-off solutions that work immediately,” Jeuland says. He also believes that intervention initiatives are too often undertaken without an understanding of local institutions, norms and preferences.

While earning an undergraduate degree in engineering at Swarthmore College, Jeuland began to appreciate that technology alone was rarely enough to create improvements in public health–that, in fact, in most cases the bigger challenge was behavior change.

His initial work in water and sanitation came as a Peace Corps volunteer in Mali, an experience that reinforced his perception of the importance of examining the physical, social and political environment in which the intervention is being conducted.

His primary project was helping develop a small-scale disposal and treatment site for septic waste. The technological aspects were relatively straightforward, he says. But there were issues with the location of the facility and with the police, who would harass and levy fines against tankers using a major road to access the site.

The result, Jeuland says: “Environmental contamination continued unabated.”

He returned to the United States and earned a graduate degree from the University of North Carolina’s Gillings School of Global Public Health, further pursuing his interests in social sciences and field research.

Upon arriving at Duke in 2010, he joined an ongoing project led by former PhD student Jennifer Orgill-Meyer, now an assistant professor of government and public health at Franklin & Marshall College, with a team that included Subhrendu Pattanayak, a Duke professor of public policy and global health, and former students Katie Dickinson and Shailesh Rai.

A collaboration with the World Bank and the regional government of Odisha in eastern India, the project was what’s called a community-led total sanitation campaign, an approach to improving the health and safety of sanitation by supporting infrastructure provision while also attempting to change behaviors. The objective was to curtail open defecation by increasing the demand for household latrines through a campaign to raise awareness of the social costs of poor sanitation.

“We were interested in seeing what would happen over the long term,” Jeuland says. “It’s one thing to get people to shift within the short term, but do they stick to those behaviors?”

What they learned was that, in this instance, people eventually reverted to their previous behaviors. Though nearly all the household latrines that had been installed were still operational four years after the intervention, many had been abandoned after 10.

There were practical reasons this was true. The latrines deteriorated and there were insufficient resources to repair them. But the researchers recognized that more work needed to be done to foster long-term behavior change.

Jeuland says the experience substantiated his conviction that a single intervention is seldom enough to create lasting change. Interventions such as that in Odisha require long-term reinforcement.

“There are no silver-bullet solutions,” he emphasizes. “There needs to be continual focus on these at-risk locations and communities. We in the international public health community need to focus more on maintaining interventions after they’ve been implemented.”

While, ideally, a foundation will be laid for local communities to themselves sustain interventions, “we still know too little about effective ways to lay that firm foundation,” Jeuland says. “It certainly isn’t easy, and studies to better understand long-term sustainability remain exceedingly rare.”

Jeuland’s focus has today shifted more toward energy. He serves as co-director of the Energy Access Project, a collaboration of Duke’s Nicholas Institute for Environmental Policy Solutions, the Sanford School and the Energy Initiative that develops energy policy and offers solutions to market challenges in emerging countries. His work addresses off-grid energy and the utilization of energy for productive purposes and income generation, primarily in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa.

This work has really brought home for Jeuland the criticality of that second lesson: context matters – for example, with a project that involves promoting cleaner and healthier household cookstoves in developing countries.

The type of stove a family uses depends upon a number of considerations, including cultural cooking practices and fuel availability and cost. “Many techno-focused or even evidence-based practitioners tend to underappreciate” such considerations, Jeuland says. “Generalizing from a few seminal studies that some technology is or isn’t useful is often dangerous.”

“It doesn't make sense to do the same kinds of interventions in all places,” he says. “You have to think carefully about how to tailor interventions to local circumstances and the local environment.”

The Energy Access Project is committed to developing partnerships with local institutions, helping nurture local capacity and gaining community buy-in for the implementation of interventions.

“I’ve learned that working alongside local partners is essential,” Jeuland says. “They often know better what’s appropriate than some researcher who parachutes in from the West.”

Bottom line: Listen, learn, adapt. And accept that change takes time.