From left: Duke students Adey Harris, Advika Kumar, Nick Haddad and Rujia Tie stand outside the health department in Pamlico County, where they spent nine weeks researching health services in the rural community. .

Published August 8, 2022, last updated on December 3, 2024 under Education News

A drive through Pamlico County in southeastern North Carolina offers glimpses of the joys of rural life. Wind rustles through tall stalks of corn along lonely country roads. In the small towns that dot the Pamlico Sound, residents take pleasure in the natural beauty, the ample fishing and the comfort of seeing familiar faces around town.

But for the county’s 13,000 residents – a mix of families that have lived here for generations and transplants – living off the beaten path can have challenges. The low-lying coastal area is prone to flooding and was hit hard by three hurricanes in the last 11 years. And like many rural communities, the county has struggled to provide hard-to-reach residents with easy access to healthcare, especially after the closing of the sole urgent care facility in 2021.

In 2011, after Hurricane Irene pummeled the region, the county formed the Pamlico County Disaster Recovery Coalition to help repair damaged homes and improve preparations for future storms. Since 1998, the nonprofit Hope Clinic has provided more than $2.5 million each year in free medications and medical supplies to those who are low-income and uninsured. But county officials know these services aren’t yet reaching everyone.

This summer, four Duke global health students spent nine weeks in Pamlico to work with county officials and partner organizations to study gaps in services and come up with more strategies to aid the most vulnerable. The team, part of the Duke Global Health Institute’s Student Research Training Program (SRT), focused on three projects: conducting a risk and vulnerability assessment for the PCDRC; assisting the Pamlico County Health Department in identifying gaps in services; and creating a community outreach plan for Hope Clinic. The students – Nick Haddad, Adey Harris, Advika Kumar and Rujia Xie – are all undergraduates at Duke, co-majoring in global health.

Leaders in the county say the students’ work provided valuable data and insights that could solidify more funding and enhanced services.

“With funding, there are better chances for metropolitan areas to be chosen because of the larger population,” says Yolanda Cristiani, executive director of Hope Clinic. “When groups like the SRT team help out, they can help collect competitive and needed data for grants, also revealing that sometimes in rural areas, patients are surviving and not thriving. Duke should be proud to have this group of students.”

Understanding community needs

While the students have studied health disparities in the classroom, the SRT project was, for most of them, the first opportunity to see those factors at work in a community. Their starting point was gathering data, which they did through interviews with county officials and staff, mailed surveys and door-to-door visits with residents, followed by analyses to pinpoint pockets of need.

“All of these interventions and things we learn in class are taught on a global level and in general iterations,” says Haddad, a junior, who is also studying environmental science. “But you don’t understand the specifics that need to be implemented for a community until you’re there.”

For Harris, a senior who is co-majoring in psychology, such community-based research was eye-opening.

“[Our team] came in with questions, but we listened to people’s experiences, learned about their needs and because of that, we could tailor the interventions better,” she says. “I learned to be open to seeking out what people need and not have a fixed mindset. The stories people shared took us beyond the questions we originally asked. It gave [our team] a better sense of what they needed.”

A cornfield outside Bayboro, N.C.,...

Students present their findings from a...

In surveys of county residents to assess disaster preparedness, for example, the students found that one-third of people they interviewed used medical equipment requiring electricity. But of those, more than two-thirds do not own a generator, making them vulnerable to health problems in prolonged power outages.

“When we were canvassing, we saw multiple challenges in the homes like someone who is elderly who lives alone or may not have transportation,” says Xie, a junior studying public policy. “More than 70 percent of homes we surveyed had at least one issue on their property.”

The team mapped vulnerable households, linking residents to the closest fire department districts for aid and showing where houses need repairs or enhancements such as ramps for those with mobility issues. From the data analysis, they suggested hosting training sessions to create disaster supply kits and evacuation plans, as well as establishing a county volunteer response brigade to aid first responders and the small PCDRC staff. When the students presented their findings at the Rotary Club in Oriental, several members signed on as volunteers.

The students “converted our experience into statistics that are helpful for funding and improvement in our delivery of service,” says Robert Fuller, chairman of the PCDRC. He moved to the area from Raleigh in 2017 after retiring. He said the SRT team’s work reminded him of the importance of following up with residents previously helped by the coalition.

“We haven’t done that before because of strained resources, but it’s an opportunity to revisit clients, find out what else they need and get them back into our system,” he says. “Rural communities make up so much of the American population, and they are underfunded and unnoticed. We’re trying to get people help.”

Filling gaps in access

At the Pamlico County Health Department, in Bayboro, Lynn Hardison is aware residents in the county face roadblocks to healthcare: the nearest 24-hour emergency department is in Craven County, a 45-minute drive for many residents. But the students’ analyses and interviews within the community honed in on more specifics. Some residents use outside county transportation systems to receive care in those areas. They also found that 14 percent of Pamlico County’s population are veterans, a group that has its own special needs.

“The number of veterans in our area surprised me, and there may be some we haven’t reached,” says Hardison, who serves as the director of nursing at the health department. “Sometimes, you can get too focused on a problem that you miss the details. Their research overall will be a tool we can use not just in theory, but in practice to reach those who may have fallen through the cracks.”

The SRT team’s research estimated 6,000-plus residents aren’t receiving care from facilities within the county, a concern for county officials. Some reasons include a lack of specialty care providers like cardiologists, limited hours at health facilities, and transportation challenges. The team suggested seeking funding for a new urgent care facility, extending hours at existing health clinics and using community health workers as a bridge between health centers and residents.

“They provided documentation to support funding for needs and develop more services,” says Hardison. “Research plays a pivotal role in helping solve problems. Without that, we won’t grow and change with people’s ages and needs.”

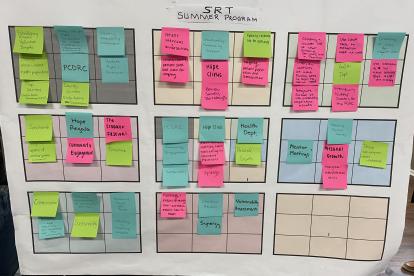

A lotus board of ideas and goals,...

At Hope Clinic, housed in the same building as the health department, the students analyzed maps to calculate transportation times to the clinic. They found that 25 percent of the clinic’s patients drive 45 minutes or more to reach it. Some patients who don’t have reliable access to transportation need to rely on rides, walk or even hitchhike to the clinic since there is no county public transportation.

The students’ analysis also identified clusters where patients live with chronic conditions such as diabetes and hypertension, showing where care and outreach is needed most. The team provided a list of more than a dozen grants to potentially fund future mobile clinics to provide care closer to these groups and support community outreach methods to enhance the clinic’s services.

Cristiani says the students were a needed resource, allowing clinic staff to focus on serving patients. Without the students’ efforts, she said she likely would have had to shorten the clinic’s patient hours to allow staff time to do the research.

‘Local is global’

The SRT research grew out of an earlier Bass Connections project, which focused on analyzing Pamlico County’s community-based response to COVID-19. That work highlighted the value in academic-community partnerships.

Both projects illustrate the value of a “local is global” approach, say DGHI professors Diana Silimperi, M.D., and Sumi Ariely, Ph.D., who mentored the Bass and SRT teams. “Global is local” recognizes health challenges anywhere are best addressed through community-based participatory research and bidirectional learning, the professors note.

“First, we hope community members and leaders gain access to critical information on local challenges, resources and solutions via evidence-based field research,” says Ariely, an associate professor of the practice of global health who helped start DGHI’s experiential learning program in 2008. “Second, our students learn fundamental issues about local health care systems and the social determinants connected to health outcomes. Many Duke global health students will go into some form of healthcare work, and we want them to understand local community health, the challenges and limitations as well as the strengths and opportunities to innovate.”

From left, Nick Haddad, Advika Kumar,...

Silimperi, an adjunct professor with DGHI, is a global health professional who has supported the implementation of large, integrated healthcare systems in dozens of low resource countries. She says rural communities in the U.S. experience many of the same challenges with healthcare access and resources. She’s lived in Pamlico County for several years and saw an opportunity to leverage the community’s strengths in helping address its challenges.

“Pamlico County is representative of other small counties that lack resources to fully address the needs of their populations,” she says. “We’re hoping to build a model in this county that utilizes lessons from global health, builds on the strengths of rural communities and offers a valuable learning experience for future professionals.”

Silimperi hopes work in the county can expand and spur a coalition of counties to improve access to care across the state’s rural, coastal areas.

A lasting partnership

During the team’s last week in Pamlico County, the students gathered at Lou Mac Park, which sits along the Neuse River in Oriental. As they reflected on their summer experience, a man approached with a basket.

“Y’all want a peach? They’re white peaches,” he asked the group. All four happily took one of the freshly picked fruits.

The man, Allen Price, is a town commissioner in Oriental and serves on the board of the Pamlico County Disaster Recovery Coalition. His appearance reminds Harris of a key thing she has learned by spending time in Pamlico.

“The wealth of knowledge people have from living here gave us a better perspective of how to approach this project,” she says. “That allowed the work to progress. You can come to a community, but without getting to know it, the work you do won’t impact it as strongly.”

Kumar, Haddad and Harris plan to continue working on projects for Pamlico during the fall semester. Xie plans to apply what she’s learned about community health in other settings, possibly during a spring semester study abroad program in Taiwan. And next summer, a new team of students will head toward the North Carolina coast, ready to build on the knowledge and ties the students have built with the partners this summer. They hope the mutual benefits of that relationship last for years to come.