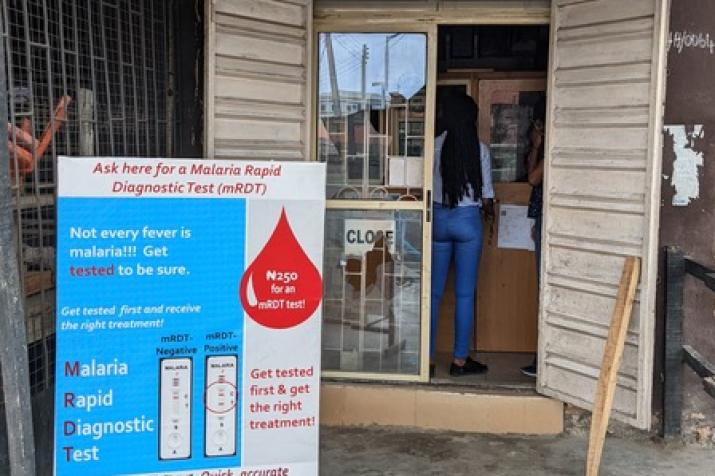

A sign outside a pharmacy in Kenya advertises point-of-care malaria testing, part of a project to reduce sales of anti-malarial drugs to people who aren't infected.

Published May 4, 2022 under Research News

When Diana Menya, MBChB, Ph,D.., was a medical student in Kenya in the 1980s, treating malaria was a simple formula. Patients who presented with a fever — one of the telltale signs of the endemic mosquito-borne illness — were handed 2500 milligrams of chloroquine tablets, an anti-malarial drug deemed one of the World Health Organization’s essential medicines and metered out as part of the Kenyan government’s policy to treat every fever as a potential sign of malaria.

Though Menya and her colleagues couldn’t have known it then, the microscopic parasites that transmit malaria were already developing resistance to chloroquine so rapidly that in some regions it would be ineffective against half of all pediatric cases within a decade. In 1998, it was removed as a first-line therapy. Another drug took chloroquine’s place. But just ten years later, microbial resistance had rendered it ineffective, too.

Now, the most effective tool against malaria is Artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACT), which along with wide deployment of insecticide-treated bed nets and spraying campaigns has led to significant drops in malaria prevalence and mortality in Kenya. But with the country’s wide network of private chemists continuing to hand out anti-malarial drugs to anyone who asks for them, Menya and others are growing worried that overuse of ACT could allow the microbes to develop a similar resistance

“If we continue doing that,” Menya says, “we’re going to run out of drugs for malaria.”

Menya, an epidemiologist with the Moi University School of Public Health, is working with DGHI associate professor Wendy Prudhomme O’Meara on strategies to address ACT overuse. One place they are focusing is on private pharmacies, which distribute most of the anti-malarial drugs used globally but rarely do testing to confirm malaria diagnoses. Studies have shown that up to 91 percent of ACTs dispensed for malaria in the private sector are purchased by people who aren’t actually infected.

As part of a pilot project, Prudhomme O’Meara’s team arranged with the Kenyan government to allow a small number of private chemists to offer rapid malaria tests to customers seeking medicines for a fever. If the customer tests positive for malaria, they are offered ACTs at a heavily subsidized price, allowing them to get the drugs for pennies. But if they test negative, they can only get the drugs at a significantly higher price.

In Kenya and Nigeria, more than half of...

“In order to reduce the rate of resistance spreading, we have to be really good stewards of this drug,” says Prudhomme O’Meara, who has led a malaria research program in western Kenya for more than a decade. “And the best way to do that is to make sure that everyone gets a parasitological test before they take the drug, and that people who have a test then follow the results of the test.”

The conditional pricing experiment is underway in 40 shops in two counties in western Kenya, with a target of reaching 6,800 people, and another pilot has recently been launched in Nigeria. Prudhomme O’Meara hopes the pilots will yield evidence that convinces public health officials in both countries and beyond to allow more rapid testing at private clinics.

Jeremiah Laktabai, MBChB, MMed, a co-investigator on the project in Western Kenya, says early results of the pilot show improved access to testing and more targeted use of ACTs. But influencing human behavior is an imperfect science, especially when what’s good for public health may not be good for the bottom line.

“At the end of the day, when testing is effective, you [may] sell less medication,” he says. “You’d wish that medical ethics and the desire to better the health of the community becomes the overarching goal.” But when a customer insists on being sold ACTs even after a negative test, many shop owners will still be all too happy to oblige, he says.

Still, if testing-based conditional pricing helps reduce overuse of ACTs by any measure, it could offer public health officials a highly scalable way to have some influence on the vast private drug market, closing the gap between those who want ACTs and those who actually need them.

“It is such a great example of implementation science,” says Prudhomme O’Meara. “We have good tools in malaria drugs and diagnostics, but they are not being used effectively. We are combining real on the ground experience, building in new expertise from economics and behavioral science, and working with policymakers on a problem that affects about half the planet.”