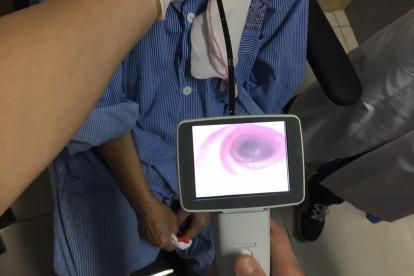

Doctors in Vietnam check out a prototype of the flexible nasopharyngoscope initially designed by Duke engineering students.

Published June 10, 2021, last updated on September 28, 2021 under Research News

A patient arrives in a clinic complaining of a sore throat. This is no run-of-the-mill case of the sniffles, and her primary doctor has already put her on two different antibiotics, neither of which managed to dent her discomfort. Now she wants the expertise of a specialist. She’s feeling desperate and more than a little worried.

If we’re in the Duke otolaryngology clinic led by Walter Lee, M.D., the next step is clear. Lee prepares a nasopharyngoscope, a long, flexible tube connected to a camera and monitor that affords him a closer look at the internal anatomy of the patient’s throat. Probably there’s nothing unusual, but maybe he sees something – a growth, a strange clump that warrants a biopsy. He might be looking at a tumor, but in that case, well, at least he caught it early.

But let’s say this is Vietnam. Most likely the doctor has the same plan in mind, but what’s missing is the flexible nasopharyngoscope, a $10,000 piece of equipment that only the most advanced clinics here own. Maybe the doctor refers our patient on to a specialist, who could be hours away. And if the patient can afford the trip and time away from work, maybe she makes an appointment. But that could take weeks, and you definitely don’t want to give cancer the luxury of time.

Lee, a professor of otolaryngology-head and neck surgery and a DGHI affiliate, has done more than a dozen medical missions in Vietnam since 2007, and so he knows this is a frustrating reality his Vietnamese colleagues regularly face. No matter how much they know, they are limited by their tools – in this case, a device so common in wealthy health systems that Lee’s clinic owns around 10.

“If the local doctors had a flexible scope, they could pick up cases earlier and get them referred for treatment,” says Lee. “I think we’d see better patient outcomes.”

It’s a problem that has bothered Lee for nearly a decade. But now, he thinks he has a solution: a low-cost version of a nasopharyngoscope initially designed by Duke engineering students. And it’s about to get its first big test.

An Engineering Problem

But let’s back up. This story really begins in 2011, when Lee received a travel grant from DGHI to explore research collaborations in Vietnam. He knew most provincial and district hospitals in the country could not afford the scopes he was accustomed to using, and that meant the doctors who often were the first to see patients complaining of nasal or throat problems had no reliable way to check for signs of cancer.

“It just seemed to be such a detriment to getting a basic head and neck exam,” Lee says. “I was thinking, how are you doing the work you are supposed to be doing without something like this?”

In fact, lack of access to such tools may be a significant reason patients with throat or neck cancers fare worse in low-income settings, Lee says. Tumors that go undetected in early screenings can grow more severe, causing irreparable damage or even death before patients are referred to specialists.

After his 2011 trip, Lee was discussing the predicament with a postdoctoral researcher, who asked, “Have you talked with Bob Malkin?”

Malkin, Ph.D., a professor of biomedical engineering and global health, teaches a series of courses in Duke’s Pratt School of Engineering on the design of medical instruments specifically for low-resource settings. Although the two professors had never met, Lee sent an email describing the problem and was pleasantly surprised when Malkin quickly responded with interest.

“This is what makes Duke such an amazing place. People are so willing to talk and share ideas,” says Lee.

What Malkin saw was a clear engineering problem his students could tackle. Medical instruments are sometimes expensive because they are designed for multiple tasks, he notes. Student engineers aren’t magicians; they can’t just make the same instrument at a lower cost. But if a client is willing to consider a simpler tool, they can often design something more affordable by stripping away unneeded functionality.

Fortunately, the tool Lee had in mind was more Ford than Ferrari. “Walter was willing to identify things we could give up to move into a lower-cost product,” Malkin says.

Malkin assigned the project in 2012 to students in his senior-level engineering course, who worked with Lee to trim down the instrument’s specifications. They quickly abandoned the tricked-out optics and motion controls that most commercial scopes use, which might be necessary in a complex case in a specialist’s office but were overkill for a basic exam.

Over subsequent semesters, new groups of seniors came on to bench-test prototypes and make refinements, such as moving the camera location, to further reduce costs. They also paid attention to the expense of cleaning and maintenance, which Malkin says is often a bigger barrier to affordability than the up-front price tag. To simplify daily upkeep, their redesigned scope can be cleaned with disinfectants commonly available in low- and middle-income countries.

Duke students lowered the resolution of...

By 2018, Malkin’s team had a prototype ready for testing on patients. Lee, meanwhile, had found an industry partner through another Dukish stroke of serendipity. A colleague at Duke-NUS Medical School connected him with Vivo Surgical, a medical device manufacturer in Singapore that has built a niche marketing instruments that expand access in low-resource settings.

With some additional tweaks from Vivo Surgical’s engineers, the Duke nasopharyngoscope was ready to manufacture. In places such as Vietnam, it will cost less than one-tenth the price of a commercial scope.

A Quantum Leap Forward

Which brings us to now, and perhaps the most important moment in the development of the low-cost nasopharyngoscope. In September, doctors at 30 hospitals in Vietnam will begin using the scopes to examine patients, putting the new design through the paces to see if it holds up to daily clinical use.

Lee, who is joining with Vivo Surgical on a five-year grant from the National Institutes of Health to conduct the clinical trial, hopes to collect data from 150,000 exams using the new instrument over the next 18 months. He notes Vietnamese colleagues who tested the scopes in focus groups have been glowing in their reviews. “They see this as a quantum leap over what they have now,” he says.

If results from the trials are similarly favorable, the next step is to get the scopes into local and regional hospitals. Enabling those frontline clinicians to perform a quick visual check will help them catch problem cases earlier, says Lee. But just as importantly, it can help them rule out more worrisome issues, saving patients the stress and hassle of a referral appointment.

“If they can use this scope to screen out patients and not have to refer them on, that helps their health system by preserving the limited resources for those who really need it,” says Lee. “We envision this as a really important tool in that early screening process.”

But in his quest to produce a more affordable nasopharyngoscope, Lee and his colleagues may have built more than just a medical device. As Malkin’s students were honing the scope’s design, Lee was knitting together a network of ear, nose and throat specialists in Vietnam, who now collaborate on a range of research projects. He has worked with the nonprofit group Resource Exchange International to develop leadership training for medical professionals in the country and has hosted several clinicians to train with him at Duke.

“This relationship is much more than just a single research project,” he says.

And that’s because, as excited as Lee is to see his long-imagined vision of an affordable nasopharyngoscope becoming a reality, it’s not actually about the tool. It’s about that patient who shows up with a worrisome sore throat, and the doctor who knows exactly what to do. It shouldn’t be the absence of a simple piece of tubing that dictates what happens next.