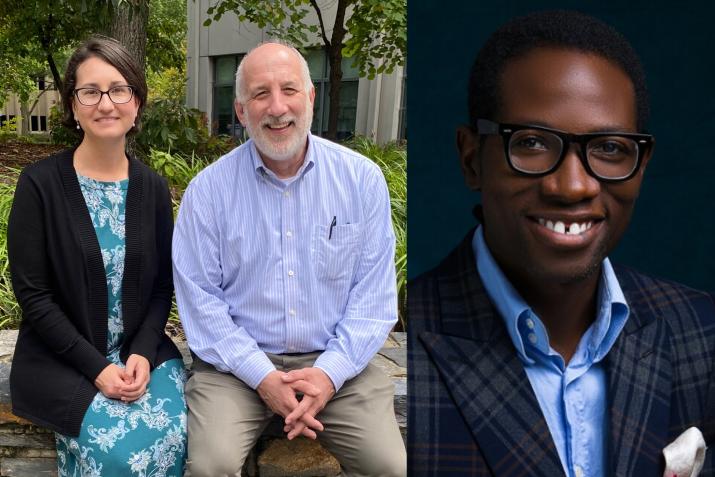

From left to right, DGHI Professors Tamara Fitzgerald and Henry Rice and University of Global Health Equity Assistant Professor Barnabas Alayande.

Published October 24, 2022, last updated on October 26, 2022 under Around DGHI

On a cloudy Thursday morning in September, Professor Henry Rice, M.D., addressed a dozen students in Duke’s Trent Hall, outlining the goals of the course they were beginning called “Global Surgical Care.” It focuses on the lack of access to surgery in many low- and middle-income countries and what health systems can do about it.

Then, Rice, a professor of surgery, pediatrics and global health, turned toward the screen at the front of the room, where the faces of several more people were displayed in the all-too-familiar Zoom grid pattern. These students, who attend the University of Global Health Equity (UGHE) in Kigali, Rwanda, are also enrolled in the class, one of a handful of courses at the Duke Global Health Institute that are taught collaboratively with international universities.

The course, partially funded by a grant from the Duke Office of Global Affairs, has drawn students and visiting faculty from across Africa, India and the United Kingdom with a range of backgrounds, including nursing, pharmacy and medical supply shipping. Their knowledge and lived experiences adds an invaluable dimension to the course, says Tamara Fitzgerald, M.D., Ph.D., an associate professor of surgery and global health who co-teaches the course.

DGHI Professor Henry Rice takes the lead...

“For Duke students, this can seem like a theoretical scenario, but for people in low- and middle-income countries, it’s real life,” she says. “One thing we tell students that take the class is we’re not teaching you about surgery -- we’re teaching you about what goes into surgery.”

Fitzgerald and Rice recall a UGHE student who took the course after his sister died from a simple surgical procedure. He wanted to understand what factors could have contributed to her death.

“It was a mic drop,” says Rice. “Global surgery is viewing surgical care, something we do every day, in the scope of financial challenges, and how does one build systems to improve on that.”

In the course, students work in teams to understand the challenges countries face in providing access to surgical care, including a lack of trained specialists, distance to surgical facilities and inadequate funding. More people die from surgical conditions than from HIV, tuberculosis and malaria combined, notes Barnabas Alayande, M.D., an assistant professor of surgery at UGHE who helps lead the course. The class projects are an opportunity for students to work together, learn and create solutions cross-culturally, he says.

“You have to look for creative ways for surgical needs to be met in low- and middle-income countries,” says Alayande. “Sometimes people can’t afford to come back to the hospital after they’ve been discharged. We want [students] to leave this course with a social commitment to global surgical care.”

Alvan Ukachukwu, M.D., took the course as a DGHI Master of Science in Global Health student in fall 2019. Ukachukwu, a native of Nigeria, says his country has limited resources in clinical staffing and supplies. He notes that fewer than 200 neurosurgeons work in the country with more than 200 million residents.

“Those are some of the reasons why I sought training in global health,” he says. “I want to see what other countries are doing differently and what solutions could work in Nigeria.”

Ukachukwu, who is now a research scholar with the Duke Global Neurosurgery and Neurology division, speaks from personal experience. As a child, he suffered a head injury after being hit by a car. While his family had insurance to pay for his care, he knew people who sold land, buildings and other property to pay for medical care. Financial challenges can increase the cycle of poverty patients face or cause them to not seek care, leading to disabilities or deaths.

“When I came into the course, I was focused on improving just workforce and equipment. But taking the course, you learn surgery goes beyond [the procedure] and is about health policy, who makes the decisions and who decides funding,” he says. “You broaden your mind and look at things without a narrow focus.”

Alayande adds, “Global surgery isn’t about a procedure on one person, but about systems. There are billions of people in the world who don’t have access to surgery, quality of care and a medical center because it’s far away or they can’t afford care. It’s staggering, but it’s real.”

Rice and Fitzgerald, who co-direct the Duke Center for Global Surgery and Health Equity, recognize what global surgery looks like now may not be the same five or ten years in the future. Both say the field is still evolving, and new leaders and ideas are emerging.

“Health problems will never go away, and there will be a need for systems to be better,” Rice says. “We’re at the start of a new science.”