Watch the full Think Global event on global medical device innovation.

Published November 9, 2023 under Around DGHI

When Julius Mugaga began working on medical device innovation in Uganda, he quickly realized he was taking on many more roles than just that of an innovator.

“Maybe today you become the quality control manager, and the next day you are the design engineer. Then another day you are a business developer,” said Mugaga, who leads the Design Cube, an innovation lab at the Makerere University College of Health Sciences in Kampala, Uganda.

Still, it’s an adventure that he hopes more global health students and scholars will embrace. “This is one of the most exciting journeys I have taken,” he said.

Mugaga shared those insights during a DGHI Think Global event on the innovation of medical devices in global health. The panel discussed three DGHI-led projects that are seeking to commercialize medical devices to address needs in low-resource settings. Mugaga is working with DGHI associate professor Tamara Fitzgerald, M.D., Ph.D., who moderated the panel, to develop a portable laparoscope for thoracic and abdominal surgeries.

Each of the innovations highlighted during the event seeks to create lower-cost devices that are better suited to the resources and conditions in low- and middle-income countries. And each has experienced unexpected hurdles as the innovators confronted challenges with testing, regulatory approvals, supply chains and manufacturing.

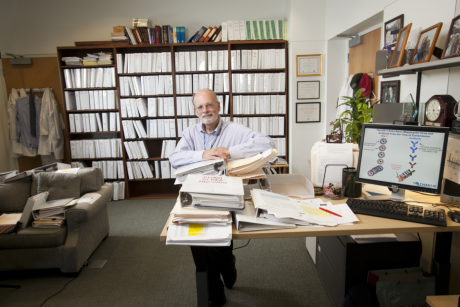

The interdisciplinary expertise of a large university like Duke can be an asset in overcoming those problems, noted Walter Lee, M.D., a professor of head and neck surgery who led the design of a low-cost flexible nasopharyngoscope to screen for throat cancers. The first prototype of the device was created by students in a biomedical engineering design class, and collaborators at Duke_NUS Medical School in Singapore helped connect Lee with an industry partner to commercialize it.

“I think me sitting here talking about this project is really a miracle, because I couldn’t have planned it this way,” he said. “There’s always an expert somewhere around here, and to be able to get some of their time and get them to buy in is really incredible.”

Marlee Krieger, executive director of the Duke Center for Global Women’s Health Technologies, pointed out that the most successful global health innovations are rooted in strong collaboration with partners in the countries where the devices are intended to be used. Krieger said it’s a lesson her center has learned through the decade-long process of developing and commercializing the Callascope, a device to aid self-administered cervical cancer screening.

“It’s really difficult to start a partnership de novo in a country where you have no connections, or Duke has no connections,” Krieger said. “I think those partnerships are incredibly important, and you really need to cultivate them.”

Panelists acknowledged the unique challenges of developing innovations in an academic setting, such as accommodating regulatory processes that weren’t designed with low-resource settings in mind and the always-present pressure to publish. But Fitzgerald noted one additional advantage to academic innovation: the opportunity to work with students and nurture their interests in global health innovation.

“For our project, doing capacity building and getting the students involved has been a big part of what we’ve done, and I don’t think industry would have been as interested in that,” she said.