Published November 16, 2018, last updated on October 11, 2021 under Research News

Early version of the Pratt Pouch.

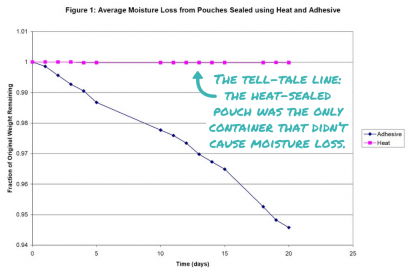

A few months before earning his degree in biomedical engineering, Michael Spohn BS’09 sat side-by-side with his advisor, Bob Malkin, at a table in Malkin’s office, staring at a graph on a laptop. The figure gave Spohn and Malkin an answer they’d been chasing for a year and a half—and launched one of the most heralded global health innovations to come out of Duke.

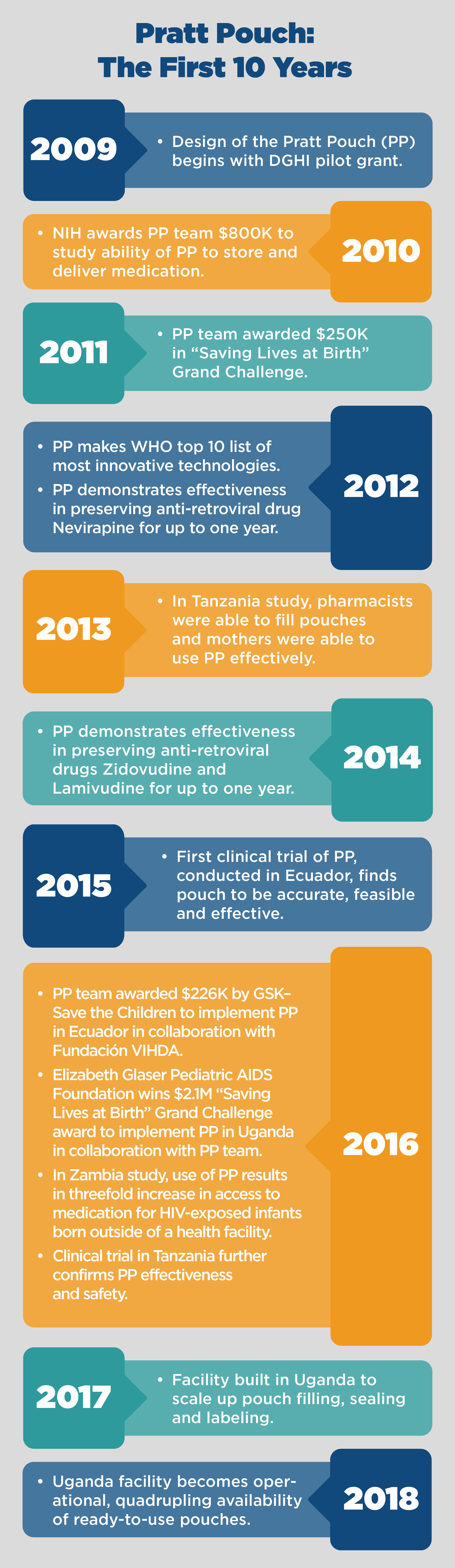

Spohn had been conducting dozens of experiments to figure out why antiretroviral medications for babies were degrading over time, a problem that was making it harder to prevent transmission of HIV to newborns in many parts of the world. The World Health Organization recommends that infants receive antiretrovirals immediately after birth, or at least within the first 72 hours, to prevent HIV-positive mothers from passing the virus through birth and breastfeeding.

In low-resource settings, where as many as half of all births take place at home, medications are usually given to pregnant women during prenatal visits, with instructions to begin giving the medication to their babies after birth. Typically, the medications are stored in plastic bottles and given to babies with a spoon, miniature cup or syringe. Not only has this made it challenging for mothers to accurately administer single doses, but the medications degrade when stored for months before the baby arrives.

Looking at the graph, Spohn and Malkin suddenly understood how to fix the problem. Spohn had been testing the effect of putting the medication into a heat-sealed pouch, an approach no one had tried before. “It was immediately clear that we’d found the solution,” says Malkin, a professor of biomedical engineering and global health.

Figure 1: Average moisture loss from...

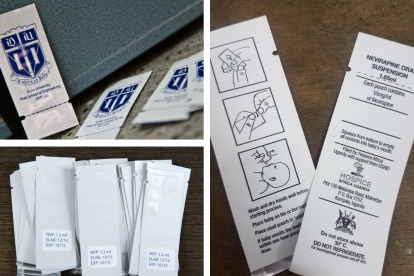

With that discovery, the Pratt Pouch was born. The pouch—a small, almost weightless, foilized packet similar to a ketchup packet—preserves a single dose of antiretroviral medicine for up to a year. A mother can squeeze its contents into her baby’s mouth in the critical hours, days and weeks after their birth. It’s currently in use in Ecuador and Uganda, and studies in four countries have demonstrated the pouch’s remarkable promise as an effective, easy-to-use and—at a production cost of four cents—inexpensive method of preventing mother-to-child transmission of HIV.

The pouch—a small, almost weightless,...

Different versions of the Pratt Pouch ...

But the pouch, named after Duke’s Pratt School of Engineering, is far more complicated than it appears on the surface. And so too is the decade-long effort that has taken the pouch and the team, including an impressive number of engineering and global health students, from idea to implementation.

That journey began in 2008, when Malkin first heard about the problem of antiretrovirals degrading in storage while chatting with a colleague at a conference. He came back to his lab determined to figure out why this deterioration was happening. He tasked Spohn with testing the two prevailing theories, which had to do with moisture loss from the medication and leaching of the parabens in the medication into the plastic containers.

Spohn tested a variety packaging vessels, including placing a filled syringe in a sealed pouch, based on previous work done by the health organization PATH. His experiments confirmed the moisture loss theory, but by a surprising mechanism. The plastic container—cup, spoon or syringe—was actually absorbing the water, causing the medication to solidify.

The high volume-to-volume ratio of the medication to the plastic of the cup, spoon or syringe was causing the medication to solidify.

“He tried many combinations, and some of them took weeks to investigate,” Malkin remembers. “Through all the experiments, one thing was clear: No matter what you did, if you included the syringe, the results were terrible.”

After the eureka moment with the graph, Spohn and Malkin started working on a pouch that would hold a single dose of the medication. It took another five years to perfect the design, whose humble appearance conceals some complex engineering.

“It’s actually a sophisticated sequence of five thin layers,” Malkin says. “You need to control the exposure to light and air, the surface-to-volume ratio and the volume-to-volume ratio and determine the optimal thickness of each layer.” The first three layers, which took about three years to formulate, are the critical components that preserve the medication.

When the team began testing the pouch with mothers in the field, the initial reactions surprised them. While foilized pouches are commonplace in Western countries, they were unfamiliar to the women in the study, and many had difficulty opening the packets without a knife or scissors.

“Our students analyzed about 5,000 opened pouches under a microscope to determine how the mother interacted with them—for example, how much tear force did she use, how long was the tear and how many failures to tear occurred,” Malkin explains. This detailed analysis, along with further testing in the field, led the team to the current Pratt Pouch design.

Malkin is quick to point out that “students, mostly undergraduates, have done almost 100 percent of the work,” which has not only kept the project moving forward but has served as real-life inspiration for aspiring biomedical engineers and physicians.

Alexa Choy BS’14, one of the students who investigated tearing practices in Ecuador, notes that “observing mothers using the pouch has left a lasting impact on me and was a critical part of my journey into pursuing a career in medicine.”

After several years of field testing, however, the Pratt Pouch has won women over. Its potential to significantly increase access to antiretroviral medication for babies is critical. Without intervention, the risk of mother-to-child transmission of HIV can be as high as 45 percent, but antiretroviral therapy at delivery potentially reduces the risk to less than five percent. And prevention gives the child the best chance at survival, as more than half of HIV-infected children die before age two.

In addition, women have deemed the Pratt Pouch easier to use and far more helpful in ensuring proper medication dosage for their babies than the conventional spoon, cup and syringe delivery methods.

A woman using the Pratt Pouch in Ecuador...

The pouch also gives women control over their babies’ fate, says Humberto Mata, co-founder of Fundación VIHDA, a non-profit organization that’s facilitating the distribution of the Pratt Pouch across Ecuador. “The women who have used the pouch are empowered,” he says. “It has helped them see themselves not as a victim but as powerful and capable of saving their child from this disease.”

And the pouch offers yet another benefit: its tiny size allows mothers to maintain discretion about their HIV status.

Broad dissemination of the pouch has always been Malkin’s long-term dream, and the team is now at a critical juncture where scale-up seems more feasible than ever. But bringing this innovation to scale has required navigating a host of challenges, from clearing regulatory hurdles to figuring out an international manufacturing and distribution plan. According to Malkin, these steps have been far more daunting than the research and development process.

The team secured FDA approval for the Pratt Pouch, but this designation doesn’t hold much stock in some countries. Each country where the pouch is introduced requires its own regulatory approval. “We’ve just seen wild variation from country to country,” Malkin says. “For example, approval can take anywhere from a few hours to a few years, and some Ministries of Health want country-specific trial data, while others find data from studies in other countries acceptable.”

The Pratt Pouch technology is open source, so theoretically, anyone with the technical expertise and equipment can manufacture them.

The pouches arrive empty in the country where they’re being used, and the process of filling and distributing them varies by country.

In Ecuador, a local hospital-based pharmacist is trained to fill the pouches using a syringe and a standard heat sealer. Fundación VIHDA, Malkin’s partner in Ecuador since 2012, facilitates the distribution of the Pratt Pouch in four hospitals in Guayquil and Quito. Women who give birth in one these hospitals receive a set of pouches immediately after they deliver their baby.

Fundación VIHDA co-founder Humberto Mata estimates that 1,000 babies have received antiretrovirals from the pouches. Mata and executive director Max Novoa are currently negotiating an agreement with Ecuador’s Ministry of Health to formalize their relationship with these hospitals.

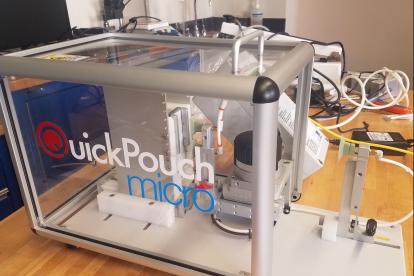

A new facility at Hospice Uganda in Kampala with semi-custom equipment fills and seals a pouch in four seconds—one quarter the time it takes to fill pouches manually.

In Uganda, where two-thirds of HIV-exposed infants don’t receive antiretrovirals, pouch filling and distribution looks quite different. In collaboration with the Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation (EGPAF), the Pratt Pouch team has recently built a high-tech facility at Hospice Uganda in Kampala with semi-custom equipment that fills and seals a pouch in four seconds—one quarter the time it takes to fill pouches manually.

Students were instrumental in bringing the facility to fruition, Malkin says. He credits two of his engineering students, Lynne Liao and Emma LaPorte, with devising the machinery concept, and Master of Science in Global Health alumna Jordan Schermerhorn MS’15 helped get the facility up and running this past summer—from troubleshooting and transporting machines to training local engineer Solomon Oshabaheebwa to assume leadership of the project in Uganda and many steps in between.

Left to right: sealing machine, opening...

A close-up of the filling machine. Photo...

Hospice Uganda building in Kampala. The...

Jordan Schermerhorn and engineer Solomon...

Check out the video above to watch the...

Once the pouches are filled at the facility, EGPAF facilitates distribution to hospitals, clinics and, ultimately, expectant mothers with HIV. Malkin and his collaborators at EGPAF hope to reach 40,000 Ugandan infants in three years.

The new facility, says Malkin, is an important turning point for the project. “We’re very excited about the potential for this automated filling process to address critical needs in countries with a high HIV burden,” he says. “Countries like Uganda, Lesotho and Botswana, where more than 30 percent of women are HIV-positive, need this larger-scale manufacturing.”

Malkin is laser-focused on expanding the use of the Pratt Pouch, both in terms of how it’s used and where it’s used.

In fact, Malkin is laser-focused on expanding the use of the Pratt Pouch, both in terms of how it’s used and where it’s used.

One of his expansion goals is to explore the potential for the pouch to be used for other medications. “For example, HIV and pneumonia often occur together, so I could imagine giving mothers two sets of color-coded pouches, one set for HIV and one for pneumonia,” he explains.

In the short term, though, Malkin wants to get the antiretroviral-filled Pratt Pouch into the hands of as many expectant mothers with HIV as possible.

To that end, he and Joanne Moore, a former vice president at Chemonics, established Pratt Pouch Consulting in 2016 to promote the use of the pouch and support governments, NGOs and the private sector in their efforts to expand access to antiretroviral medication for babies born to women with HIV. Malkin provides technical support, while Moore focuses on identifying new funding sources and partners and helping organizations integrate the pouch into their programs. Malkin and Moore are currently looking at implementing the pouch in Nigeria and Mali.

“Our goal is to make Pratt Pouch part of the health systems responses to mother-to-child transmission, rather than a standalone initiative,” Moore says.

Want to hear more about the science behind the pouch? Read the studies!

- A Foilized Polyethylene Pouch for the Prevention of Transmission of HIV from Mother to Child (2012)

- A Pouch May Prevent the Transmission of HIV from Mother to Child (2013)

- Foilized Pouches Can Prevent the Transmission of HIV from Mother to Child Using Multi-Drug Therapies (2014)

- Accurate Dosing of Antiretrovirals at Home Using a Foilized, Polyethylene Pouch to Prevent the Transmission of HIV from Mother to Child (2015)

- The Pratt Pouch Provides a Three-Fold Access Increase to Antiretroviral Medication for Births outside Health Facilities in Southern Zambia (2016)

- Providing Safe and Effective Preventative Antiretroviral Prophylaxis to HIV-Exposed Newborns via a Novel Drug Delivery System in Tanzania (2016)

NOTE: Photos of mother and baby using the Pratt Pouch by Marc-Grégor Photography.